Boubacar Bah crossing the Cogon River. Photo by Souleymane Camara.

Frontline Voices in the Fight for a Just Energy Transition – Part 1

24/11/2025

Bauxite, the mineral used to make aluminum, is a major source of revenue for the West African country of Guinea. But bauxite mining has displaced and impoverished thousands of people living near project sites. As Guinea’s oldest mine prepares to expand—driven by growing global demand for aluminum for use in electric cars, solar panels and batteries—communities in its path are demanding a fairer deal.

When Ibrahima Diallo was a boy, he dreamed of leaving his village in rural Guinea and moving to the city. At age 20, he summoned the courage to travel to neighboring Senegal, where he settled in the bustling coastal city of Saint Louis. He opened a convenience stall selling snacks and drinks and embraced the excitement of urban life. But the city gradually wore him down—money was tight, and the din of traffic and people never seemed to relent—and he found himself missing the quiet of his home village, Teliwora.

“I was determined to stay in Senegal and make a good life. But the longer I stayed, the more I missed home. I worried about my parents. So I came back,” he said, speaking in Pular, the local language, with a hint of the Senegalese accent he acquired after five years of living abroad.

Since returning to his village, Ibrahima Diallo, now 35, has re-embraced the rhythms of rural life that he grew up with. He lives in his boyhood house, a thatched mud hut tucked under a canopy of soaring trees. Like his neighbors, he farms rice, corn and other crops on the family plot, using the slash, burn and rotate approach he learned from his parents. His goats graze on the nearby bowal, elevated grass-covered plains that local people manage communally to graze their livestock. During the dry season, when the fields are fallow and food is scarce, he goes to the forest to forage for nuts and fruits.

Residents of Teliwora.

Like many villages in rural Guinea, Teliwora lacks electricity, plumbing and a reliable internet connection, limiting economic development. But the land provides enough food and water to sustain life and a tight-knit social system, as it has for generations.

“Experiencing the city and then coming back to the peace and nature of Teliwora has made me realize that I love it here more than any other place in the world,” Ibrahima Diallo said. He has married and hopes to raise children in his village.

Ibrahima Diallo lives in northwestern Guinea, which is known for its red clay soil. The region is also home to one of the world’s largest deposits of bauxite, the mineral used to make aluminum, the lightweight metal that underpins much of modern life. Aluminum is ubiquitous in the world’s cars, airplanes, technology and food packaging.

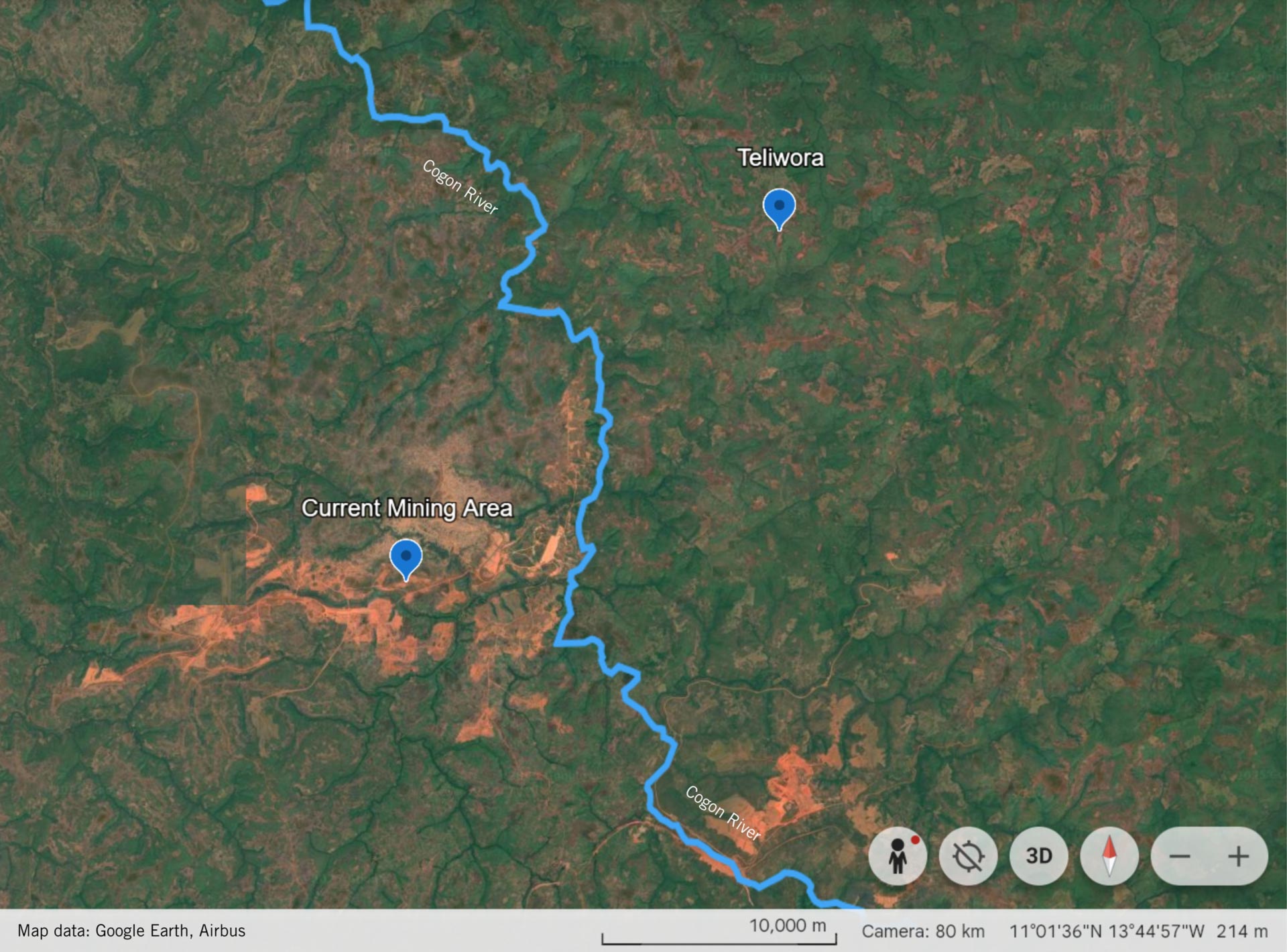

The region’s bauxite deposit is divided in two by the Cogon River, which flows west into the Atlantic Ocean. The area south of the river has been heavily strip mined for decades, devastating the landscape and displacing thousands of people.

Guinea is home to the world’s largest population of endangered western chimpanzees, but their habitats in the Boké region are increasingly threatened by bauxite mining.

In mining areas, yawning brown pits stretch to the horizon, stripped of all signs of life, with trees, fertile topsoil and entire villages cleaved from existence.

But the land to the north, where Ibrahima Diallo lives, has so far been insulated, even though it is within mining concession areas. This is largely due to the Cogon River, whose waters swell in the rainy season, creating a de facto barrier to mining. The area has remained pristine, with hundreds of small villages like Teliwora dotting the landscape, connected by a patchwork of rutted dirt roads that wind through rocky plateaus and forests. The area is home to rich biodiversity, including critically endangered chimpanzees.

The Cogon has insulated villages and pristine nature north of the river from the impacts of bauxite mining, which has devastated areas to the south. Ibrahima Diallo fears his village, Teliwora, is in the path of a planned mine expansion.

This untouched ecosystem, shielded from mining for so long, is now at serious risk of being ravaged by the global hunger for bauxite. As large economies in Europe, North America and East Asia decarbonize their transportation and energy systems, aluminum will play a key role in this transition to renewable energy sources. Aluminum accounts for nearly 20 percent of the weight of metals used in a typical battery for an electric vehicle. Making those vehicles lighter and more energy efficient will require metals like aluminum in place of heavier materials like steel. Aluminum is also a key material in renewable energy technologies such as solar panels and wind turbines.

This has placed the lush ecosystem north of the Cogon—and the people like Ibrahima Diallo who depend on it—in the crosshairs of what could be the Guinean bauxite industry’s most significant expansion since large-scale mining began here in the 1960s. The country’s oldest mining company, Compagnie des bauxites de Guinée, or CBG, is exploring for bauxite in 85 villages north of the river, including Ibrahima Diallo’s, in what local people fear is preparation for full-scale mining.

“We are worried about mining coming to our land. I have seen the areas that have been mined south of the river. It is total destruction. The forest, the water—everything has been destroyed. Life is not possible there,” Ibrahima Diallo said.

He continued: “We have heard that when mining companies come to a village, they act like the land belongs to them, and they just take what they want. But they should know that our ancestors lived on this land for many generations. We inherited it from our fathers. It’s our heritage. We live here, so it belongs to us.”

“I have seen the areas that have been mined south of the river. It is total destruction.”

–Ibrahima Diallo

A handful of multinational-owned firms, including CBG, dominate Guinea’s bauxite sector. They mine the bauxite, a reddish‑brown metal found in porous rocks several meters underground, by stripping the top layer of earth using excavators and bulldozers and then extracting the ore by dynamite blasting and specialized surface miners. The bauxite ore is then put on trucks for transport to purpose-built railways, which carry it to nearby ports. The firms ship the vast majority abroad for refining and smelting into aluminum.

Guinea supplies 22 percent of the world’s bauxite. Bauxite mining has contributed billions of dollars to the Guinean government’s budget. Yet despite its importance globally and domestically, the bauxite industry has done little to help the average person in Guinea, which ranks near the bottom of the UN’s Human Development Index.

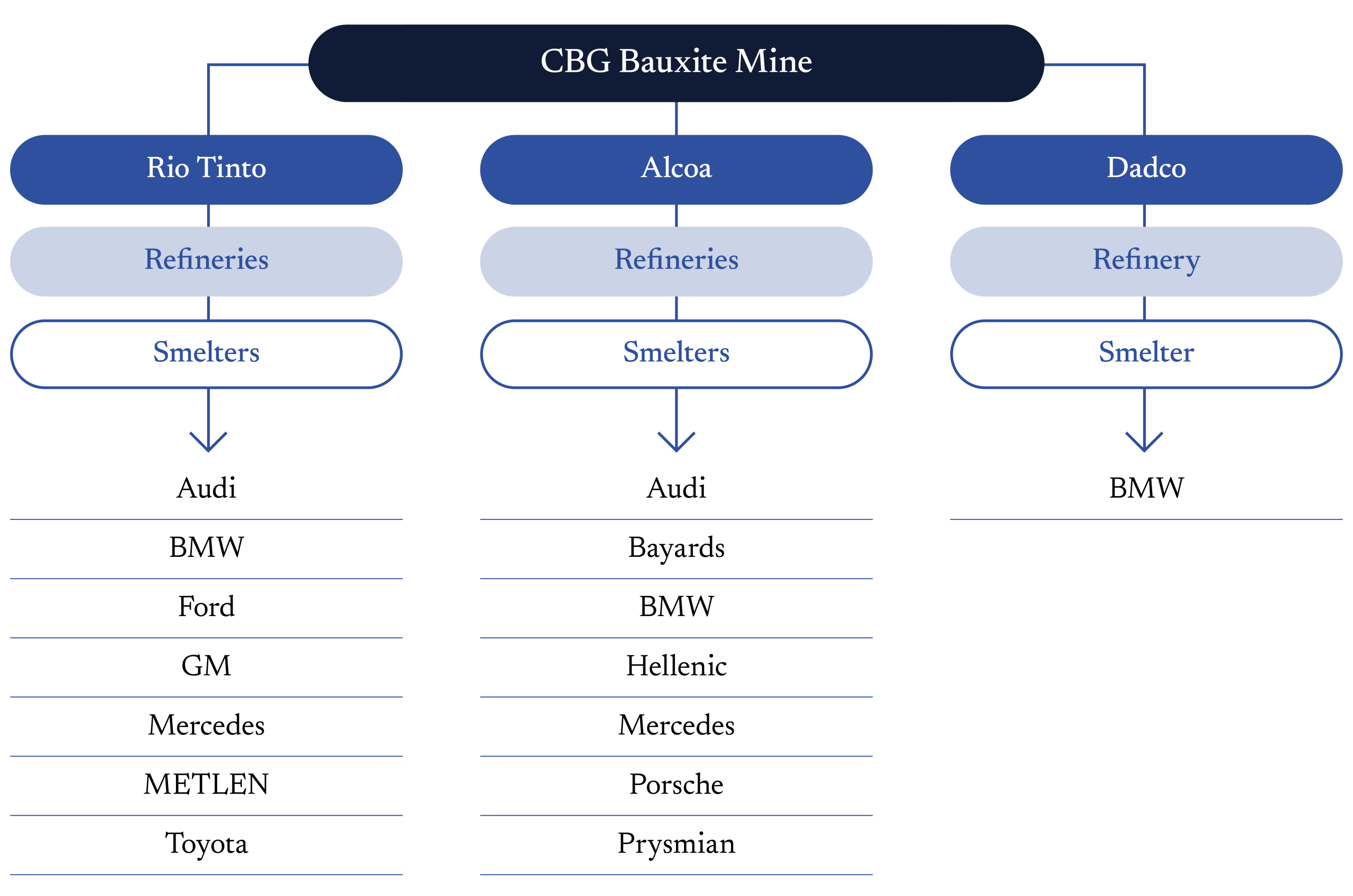

CBG is a joint venture controlled by the U.S. aluminum giant Alcoa, Australian-British miner Rio Tinto, a privately held firm called Dadco with interests in Germany, and the Guinean government. For decades, the company has been a singular presence in this part of Guinea, dominating nearly every aspect of life there since it began mining in 1973.

The company has its own railway and power plant, anomalies in a country with poor transportation and electricity infrastructure. CBG even operates its own radio station that plays the latest pop hits from Senegal and Nigeria mixed with announcements praising the company’s positive impact on the community.

CBG’s mining concession is nearly 3,000 square kilometers, an area larger than Luxembourg. The company has conducted mining operations in roughly one quarter of that area, to devastating results for local people and the landscape. CBG has expropriated farmland, polluted water sources and caused long-term damage to the livelihoods of people near mining sites, according to Human Rights Watch. It has done so without the consent of those in its path.

Approximately 10 percent of the land that CBG has mined has undergone some form of rehabilitation, far below industry best practice, according to an analysis of satellite imagery commissioned by Inclusive Development International looking at data between 1974 and 2019. This has left behind vast dead zones that are useless for agriculture or raising livestock, the primary economic activities in the area. Runoff from strip mining pollutes rivers and springs, which people, crops and livestock rely on for water.

Trucks carrying bauxite away from the mining site.

Affected people have received little tangible benefit from CBG’s multibillion-dollar operations, leading to widespread disaffection and demonstrations that have occasionally turned violent.

And now, driven by the global demand for aluminum to feed the renewable energy transition, CBG has turned its attention to the pristine landscape north of the Cogon River. In recent months, a flurry of activity—convoys of CBG-badged trucks fanning out on dirt roads, village visits by company representatives, talk of exploration drilling—suggests that CBG is preparing to expand. The company estimates that it will need to increase its annual bauxite production by a third over current levels to meet the demands of the renewable energy transition, its then director said in a speech to Guinea’s Chamber of Mines in 2023.

The situation in Guinea is similar to that faced by rural communities in other parts of the world. From the salt flats of Chile and Argentina, to the tropical islands of the Indonesian archipelago, to the deserts of the southwestern United States, rural and Indigenous communities sit on top of vast deposits of the lithium, nickel, bauxite and other metals deemed necessary for the renewable energy transition.

Teliwora.

On the one hand, these communities—which rely on subsistence farming, livestock herding, hunting and fishing—have contributed virtually nothing to the global carbon emissions that are warming the planet. On the other hand, they are among the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which will impact the rural poor hardest. In an especially cruel twist, a key solution to a problem that they did so little to cause is found under the very land they have occupied, in many cases, for generations.

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, an industry source, estimates that nearly 300 new mines will be needed by 2030. This explosion of mining will threaten potentially millions of people and delicate ecosystems. While plenty of social and environmental standards exist in the mining industry—covering all manner of players, from the miners themselves to their financiers, investors and buyers—these guidelines have rarely resulted in satisfactory outcomes for people in the path of mining.

In Guinea, people north of the Cogon River understand that the arrival of mining will affect their lives dramatically.

At a more basic level, these standards have largely failed to prevent catastrophic harm to communities and the environment. In its scramble for critical minerals necessary for the energy transition, the mining industry threatens to repeat that pattern of mistakes—but at a much faster pace than before—unless it dramatically reforms its approach.

In Guinea, people north of the Cogon River understand that the arrival of mining will affect their lives dramatically. But pinpointing precisely how—what CBG’s arrival might mean for their villages, their families and their way of life—has proven difficult.

Djouma Bobo Diallo, a farmer from the area, said CBG representatives have provided little clarity about the company’s plans during visits to his village. “They told us they would do some exploration work, and that if they caused damage, they would compensate us. But we don’t know how much compensation they will provide and who will get it. And we don’t know if they will return to start mining, or where they will mine. They have told us little,” he said.

Could the arrival of mining provide their villages with the basic services that they desperately needed?

Some people in the area have come to expect the worst, based on what they have seen and heard from relatives and friends whose lives have been upended by mining in areas south of the river.

“If this happens to us—if CBG destroys our land, streams and rivers like they have done on the other side of the river—we are as good as dead,” said Boubacar Bah, who lives near the banks of the Cogon in a village called Nd’antary Mborou.

In addition to fear and uncertainty, some people also sensed a hint of opportunity in the looming change. Woven into the stories of destruction and despair told by people affected by mining, they had heard some positive accounts that gave them hope that mining might somehow benefit them.

They wondered: Could the arrival of mining provide their villages with the basic services that they desperately needed—electricity, clean water, internet access, sealed roads, schools and health clinics—but were out of reach for rural communities like theirs?

“Living conditions in my village are difficult,” said Momadou Lamarana Bah, also from Teliwora. “If CBG comes, perhaps they can help us improve our quality of life. We want them to build a school, a health clinic and wells for fresh water. And the roads are so bad—we need better roads.”

He paused to consider these requests. “Based on what I’ve heard, CBG can provide these things. But what will we have to give up in exchange?” he said.

Another man, Alpha Oumar Diallo, said he didn’t trust CBG to provide these things. He’d prefer for the company to employ local young people, so that they can provide for themselves and their families for years. “If CBG employs our children, then we will be taken care of for the rest of our lives,” he said.

“If this happens to us—if CBG destroys our land, streams and rivers like they have done on the other side of the river—we are as good as dead.”

–Boubacar Bah

Ibrahima Diallo, the man who emigrated to Senegal but returned home, said that if CBG starts mining in the area, thousands of lives will be in the company’s hands. “If they take the land we depend on, they have a responsibility to give us something better,” he said. That could be infrastructure, employment, or a share of revenue from the mine that the community could manage and spend based on its needs, he said.

But ultimately, he wants local communities to have the ability to negotiate those terms on equal footing with CBG. “We are ready to discuss our ideas with CBG,” he said.

More than anything, though, Ibrahima Diallo longs to stay in the village he once left as a young man, but whose quiet beauty drew him back. “I will do anything to stay here,” he said.

Boubacar

Boubacar Bah resting beside the Cogon River.

Boubacar Bah, 40, comes from a family of leaders. His father and grandfather were chiefs of his village, Teliwora, a rural community in Guinea several hours’ drive from the nearest town. People still praise his father, who died six years ago, for prioritizing education and building a brick school.

Because of this lineage, he feels a deep connection to the land—and a responsibility to protect it. “My ancestors farmed this land. My grandfather lived on it, my father too. This land belongs to us,” he said.

Forgoing a future in local politics, Boubacar Bah followed a different path that honors his father’s commitment to education: He became a teacher of Islam. He spent seven years learning Arabic so that he could read aloud passages of the Quaran in Pular, the local language, to people in the area.

He has traveled as an educator throughout northwestern Guinea, the epicenter of the country’s bauxite industry. He has observed firsthand the ravages of CBG’s operations, the country’s oldest bauxite mine. Relatives from mining areas have in recent years begun journeying to his village to grow crops on his land, telling stories of damaged farmland and food shortages back home.

“When I hear this, I worry that the same thing will happen to us,” he said.

CBG representatives have visited his village and inventoried his property in preparation for bauxite exploration. Recently, they gave him a laminated card itemizing several of his cashew trees that are in the exploration zone. He has been told that he’ll receive compensation for these trees, which are likely to be destroyed.

Boubacar Bah with his neighbors in Teliwora.

“My ancestors farmed this land. My grandfather lived on it, my father too. This land belongs to us.”

–Boubacar Bah

CBG representatives have never asked him or his neighbors for permission to work in their village, Boubacar Bah said. Nor have they discussed the potential wider damage to homes, water and farmland that is likely to occur if bauxite mining moves forward.

“If it were up to me, they would not touch our land,” he said. “But I am realistic: I know CBG will come to mine here. When they do, they must respect our rights. This is our land, so we should benefit. This is normal.”

Boubacar Bah has thought a lot about what kind of deal would be fair to his community. Ultimately, it’s not complicated for him: CBG should share the true value of the land—and what lies beneath it—with the people who have occupied it for generations.

“Whatever the bauxite on our land is worth, CBG should get half, and we should get the rest. We would use that money to improve our living conditions. We would build a health clinic, a youth center. We would buy livestock and machinery to make our farms more productive,” he said.

Touching on a topic close to his heart, he added: “The school my father built is in decay, and there is only one teacher. We would repair it and hire more teachers to educate our children.”

Boubacar Bah acknowledged that nothing in CBG’s track record suggests that this would come easily. “We know that CBG is more powerful than us,” he said. “But the people of Teliwora are strong and united. We are not afraid to stand up for our rights.”

To expand to the untouched side of the Cogon River, CBG will require a significant injection of capital. The company will need to build roads and bridges so that its equipment and trucks can reach far-flung bauxite deposits. It will also likely need significant upgrades and further development of its infrastructure. This will be expensive.

The last time CBG expanded, in 2016, it borrowed $863 million to cover the costs. Nine banks jointly provided the loan, led by two development finance institutions: The World Bank’s private-sector arm, the International Finance Corporation, and the U.S. government’s Development Finance Corporation (at the time called the Overseas Private Investment Corporation), which together covered nearly half of the amount. Five large European commercial banks and two smaller Guinean banks also joined. The loan was partially guaranteed by the German government, which wanted to ensure a steady supply of bauxite for its car industry.

The involvement of the development finance institutions was supposed to ensure that CBG’s operations were environmentally and socially responsible. The project would adhere to the International Finance Corporation’s environmental and social Performance Standards, a leading international benchmark for managing environmental and social risks in development projects.

Yet in practice, the mine was anything but responsible. CBG largely ignored the rights of people living in and around the mining zones, treating community land as state property that it could seize without permission from local people, despite the International Finance Corporation’s requirements and Guinea’s 1992 Land Law recognizing the customary land tenure of local communities. CBG provided limited compensation, but only for trees and crops—not the land itself.

CBG has only recently recognized the customary land rights of local communities and made efforts to bring its land acquisition policy in compliance with the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards. It has made a commitment to compensate affected communities for the land taken after the International Finance Corporation’s loan, but it has not done so yet. Meanwhile, CBG has made no such commitment to address the economic displacement caused by its land-taking in the period before the 2016 loan.

To effectively address these problems, CBG would have had to tackle them before mining started.

Years of land grabs have devastated the lives of people in the mine’s path. Without fertile soil to farm and deprived of access to clean water and grazing areas for their livestock, thousands have experienced declines in their living standards. Ramboll, an independent environmental and social monitor that reports to CBG’s lenders, found recently that “the risk that livelihood restoration will not be possible for some communities is considered to be high with the potential that communities will be dependent on CBG for survival (through continuous food assistance) and that grievances multiply.”

The experience of one village, Hamdallaye, encapsulated CBG’s approach. In 2020, at the outset of the COVID pandemic, the entire community was physically moved to a new area that CBG had previously strip mined and hadn’t properly rehabilitated. Villagers were given replacement houses, but the unproductive and poorly rehabilitated resettlement site did not offer them opportunities to restore their traditional livelihoods. While CBG contractors have put in place livelihood support projects, these have largely failed.

For other villages in the mine’s path, the situation has been even worse. Without adequate mitigation measures to protect the natural resources that local communities rely on, the destruction of rivers and agricultural land and the dust from mining have made life in these villages untenable. Meanwhile, CBG has failed to implement effective programs to restore village livelihoods to pre-mining conditions, despite its obligations under the standards it agreed to with the International Finance Corporation and other international lenders.

“I could talk until the sun sets, and that still wouldn’t be enough time to describe all of the problems mining has caused,” said the resident of a village affected by CBG’s expansion, who asked to remain anonymous to protect against reprisals. “In the past, we had farmland. We fished and hunted. We had food. We had a good life. None of this exists anymore. The only thing left is suffering.”

Bauxite mining.

Fed up and calling for justice, residents of 13 villages filed a complaint to the International Finance Corporation’s independent watchdog, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, in 2019. The complaint noted that “[f]or many of the complainants, years of damage from CBG’s activities, particularly loss of land and water sources, has gradually eroded living standards and economic resiliency.” Three of the co-publishers of this report, Inclusive Development International, International Trade Center for Development (CECIDE) and Association for Rural Development and Mutual Aid of Guinea (ADREMGUI), supported 540 community members in filing the complaint.

The International Finance Corporation’s ombudsman initiated a dispute resolution process between the complainants and CBG that sought to address local concerns. The years-long process, which is ongoing, has been grueling for everyone involved and often frustrating for the complainants.

The two sides have managed to reach several agreements that have brought change, including the establishment of 1,000-meter buffer zones between villages and dynamite blasting and the construction of wells that have improved access to clean water. But most of the damage remains unaddressed, due to the high cost and technical complexity of remedying the extensive impacts of mining, especially when they are left to fester for years. To effectively address these problems, CBG would have had to tackle them before mining started, during the project design phase, which it did not do.

Before we filed the complaint, CBG did whatever they wanted and didn’t talk to us at all. Now, if they want to do something, they at least call the community and inform us first. This is a big change.”

–Sekouna Bah

While progress in remedying harm has been stubbornly slow, the complainants have noticed one significant outcome of the mediation process: CBG has made some positive changes in how it interacts with local people. “Before we filed the complaint, CBG did whatever they wanted and didn’t talk to us at all. Now, if they want to do something, they at least call the community and inform us first. This is a big change,” said Sekouna Bah, a community representative in the mediation process.

This change in attitude has come about through years of hard negotiations by community representatives and their NGO advisors, Inclusive Development International, CECIDE and ADREMGUI. The complainants have refused to back down in the face of a multibillion-dollar mining operation backed by Guinea’s military-controlled government.

They have stood up for their rights by calling on CBG’s sprawling web of investors, financiers and customers to fulfil their responsibility to exercise their leverage with the company to address human rights impacts and change how it treats local people.

Women gather in a village south of the Cogon River.

CBG’s business partners will have substantial leverage to demand that it acts responsibly and negotiates with people in the mine’s path.

Many of CBG’s business partners, including the car companies that use its bauxite in their vehicles, say they now recognize that the company has failed to act responsibly and have called on it to respect the rights of local communities.

In a statement shared with CBG and the other participants in the mediation, Volkswagen, Audi and Porsche wrote: “We clearly expect compliance with internationally accepted human rights, compliance and environmental standards. This includes the respect for legal and customary rights and the interests of local communities in their lands and livelihoods as well as their use of natural resources.”

They will soon get another chance to assert their expectations if, as expected, CBG moves forward with its plan to expand north of the Cogon River. CBG’s business partners will have substantial leverage to demand that it acts responsibly and negotiates with people in the mine’s path, before mining starts, to avoid harm and provide real benefits.

CBG’s lenders, including the International Finance Corporation, have been kept abreast of exploration activities north of the river by the third-party monitor, Ramboll. The lenders are financially backing those exploration activities under the terms of the 2016 loan, according to public disclosures, and those activities must comply with the International Finance Corporation’s environmental and social Performance Standards.

If CBG decides to start mining north of the Cogon River, it must get permission from these lenders before doing so, according to Ramboll’s monitoring reports. Moreover, CBG is likely to approach many of these same banks—including the commercial lenders Société Générale, BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole, Natixis and ING Bank—for hundreds of millions of dollars in additional financing to build the infrastructure necessary to expand. That gives these banks substantial financial leverage over how CBG designs and manages the next expansion.

Meanwhile, many multinational companies that use CBG bauxite in their products have human rights and environmental standards that firms in their supply chains must follow. This includes the car companies Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi, GM, Ford, Toyota and Porsche, which manufacture electric vehicles. It also includes companies involved in renewable energy, including Hellenic Cables, which supplies green energy projects; Bayards Alumnium Solutions, which produces aluminum parts for wind turbines; and METLEN, which builds and develops clean energy projects.

While these firms do not source bauxite directly from CBG, research conducted by Inclusive Development International shows that they purchase aluminum or aluminum products containing bauxite produced by CBG. Audi and BMW, in written responses to questions for this report, noted that they did not have direct supply relationships with CBG. However, they did not dispute Inclusive Development International’s research showing that they are indirectly sourcing aluminum containing CBG bauxite through third parties.

CBG’s Bauxite Supply Chain

Bauxite from the CBG mine is refined and smelted into aluminum that is used globally by car companies and firms that supply renewable energy projects.

“Most of these things are solvable. But there’s a perception within mining companies that these things cost too much.”

–Anna Quillinan

The most power, though, is in the hands of the shareholders of the CBG joint venture. Collectively, Alcoa, Rio Tinto and Dadco hold a 51 percent stake in the company. They also sit on CBG’s board of directors and advise on its operations. Perhaps most important, Rio Tinto, Alcoa and Dadco are effectively CBG’s only direct customers: They acquire the vast majority of its bauxite and send it through their vertically integrated processing and supply chains. If these firms were to demand change, CBG would have no choice but to follow suit.

Inclusive Development International emailed questions and offered an opportunity to comment on the findings of this report to CBG, its shareholders and financiers, and the companies in its supply chain referenced above. Company responses can be viewed in full here.

Anna Quillinan, the CEO of an Australian mining firm called Spektrum Development, said that many of the problems that CBG has caused in the past could be solved in future mining areas with engineering solutions. For instance, the sediment run-off that has polluted waterways south of the Cogon could be dramatically reduced before mining starts in the north by building earthwork boundaries that better contain waste and treating affected water at plants before pumping it back into the surrounding environment. In addition, CBG could much more rapidly rehabilitate land after the bauxite has been extracted, allowing farmers to use it productively again.

“Most of these things are solvable. But there’s a perception within mining companies that these things cost too much,” said Quillinan, an engineer who has worked in the industry for more than two decades.

That thinking is flawed, she said, because it doesn’t account for the hidden costs of ignoring legitimate community concerns, which mining companies ultimately must bear. The industry’s top-down approach to addressing these concerns—in which engineers and consultants impose minimally viable mitigation measures on affected people, rather than collaborating with them—reduces up-front project costs. But this leads to community resentment and resistance, eroding the long-term value of the mine, which is seldom factored into a project’s overall cost.

According to Quillinan, the better approach is for mining engineers to engage directly with communities from the outset, so that they better understand their way of life and concerns. This would help them design engineering solutions that reflect actual conditions on the ground. “This builds trust and cooperation and then, hopefully, support for the mine, as opposed to protests,” she said.

In addition to managing negative impacts, also essential to securing local support is to ensure that affected communities actually benefit from mining on their land. In interviews, people living north of the Cogon River shared many ideas about how this could happen, including communities receiving a share of the mining revenues, which they could manage and use to build schools, health clinics and better housing; training programs and employment opportunities for young people; improved access to electricity, clean water and mobile phone networks.

Rio Tinto and Alcoa, key players in the CBG mine, have track records of reaching such benefit-sharing agreements with local communities in other parts of the world.

Rio Tinto and Alcoa, key players in the CBG mine, have track records of reaching such benefit-sharing agreements with local communities in other parts of the world. At Rio Tinto’s Gove bauxite mine in Australia, following years of conflict and litigation, the company and local leaders negotiated a 42-year lease agreement that provides traditional landowners with 15-18 million AUD per year to fund community initiatives, including infrastructure projects and employment opportunities, according to an online database of Indigenous land agreements in Australia. In Brazil’s Pará state, Alcoa addressed local protests by agreeing to a deal with local ribeirinhos communities to pay rent for occupying community land, compensate for losses and damages, and give locals an annual share in mine profits, according to media reporting. While neither of the deals put an end to all of the controversies and negative impacts caused by the mining operations, they brought tangible benefits to local people.

Momadou Lamarana Bah, who lives north of the Cogon, said any agreement with CBG must start from a simple principle: “If CBG takes our land, they should improve our lives.”

Kadiatou

Kadiatou Bah.

The threat of mining has loomed over Kadiatou Bah, 70, for nearly all her life. One of her earliest memories is of a white plane circling her village, a startling sight in rural Guinea in the 1960s. “We didn’t know who was in that plane. Somehow, though, we knew that they wanted our land,” she said.

She was seven at the time and spent her days caring for the family cattle and playing with her cousin beneath the towering mango trees of her village, Horé Lari. There were further sporadic visits over the years from people she now understands to have been from the country’s oldest bauxite mining company, CBG. But the mining that many feared would arrive never did.

Kadiatou Bah is now a grandmother of 15. Life in her village has changed little since her days as a girl during the years after independence from France.

“The biggest difference is the houses. There were only small mud huts when I was a girl. Now some people have brick houses with metal roofs,” she said. Her father, a respected leader at the mosque, once led the daily call to prayer with only the power of his lungs; now it comes amplified from a recording.

Life has otherwise remained mostly the same. The village still lacks electricity, and access to the outside world remains limited by rough dirt roads and a poor mobile phone connection. The daily rhythms haven’t changed since Kadiatou Bah’s birth: children still graze livestock on the grassy plateaus, women fetch water from the streams, and men tend crops on family plots.

Horé Lari.

“This land is ours. We inherited it from our fathers. We want to pass it on to our sons. We should decide what happens to this land.”

–Kadiatou Bah.

The arrival of CBG threatens to forever alter those rhythms. “I have heard that it is very ugly where CBG has mined. They have taken land from people and given them some money to build a house. But a house is not enough: Those people don’t have enough money to live. We are afraid that this will happen to us,” she said.

CBG has done little to assuage those fears. Company representatives have been tight-lipped about their plans in recent visits to the village. “They have never explained why they are here, why they want our land,” she said.

Kadiatou Bah has had a lifetime to think about what should happen if mining comes. “This land is ours. We inherited it from our fathers. We want to pass it on to our sons. We should decide what happens to this land,” she said.

Sekouna Bah in his village, N’danta Fognè.

In May of this year, leaders of several villages north of the Cogon River met in a conference room outside of the town of Sangaredi, where CBG’s operations are based. The leaders wanted to think through how to respond to the looming threat of mining, which seemed to be gathering pace.

Joining the leaders from the north were community representatives from south of the river who were involved in the dispute resolution with CBG, along with the NGOs supporting them in the mediation. The leaders from the south were there to shed light on what it had been like for CBG to take their homes and farmland, pollute their water, and undercut their standards of living—and how it felt to stand up for their rights across the negotiating table. They knew what may await their compatriots and wanted to offer advice and, where possible, strength and encouragement.

Sekouna Bah, a lead negotiator in the mediation who comes from a mining-affected village called N’danta Fognè, said the fate of people living in the north was deeply personal to him. “My mother is from a village north of the Cogon River, and I feel a connection to the communities there. People from the south believe that our ancestors come from the north. We want to do everything we can to help them,” he said.

In 1986, two years before he was born, CBG razed his family’s village and its 80 houses and moved everyone to another area, to start their lives from scratch. CBG compensated the community with a total of 3 million Guinean francs—a paltry $3.75 per house using today’s conversion rates. In the years since, CBG has steadily encroached all over again on the new village’s farm and grazing land and polluted its fresh water sources.

Sekouna Bah said he wanted to prevent this from happening to others. “I can’t stand by while they keep doing this to people,” he said.

In the meeting room, over the course of three days, leaders from the south shared similar stories and discussed in detail what had happened to their lives since the arrival of mining. They advised people in the north to learn their rights and to organize themselves to stand up for one another.

“Your voice is the only thing you have. You must use it,” Sekouna Bah told the participants.

The NGOs shared information about CBG and its business partners, including the human rights standards they claim to uphold when interacting with local people. This includes the International Finance Corporation Sustainability Policy, which requires the International Finance Corporation to assess whether its clients like CBG have obtained “broad community support” for their projects.

CBG had utterly failed to meet that standard in its dealings with communities, leaders from the south said. “When they came, they just took our land. They didn’t ask us for permission,” Sekouna Bah said.

Bauxite mining site south of the Cogon River.

“We know that CBG wants to profit from our land. But we should also profit.”

–Ibrahima Diallo

Another leader from the south, Kounsa Baïlo Barry, said that if he could go back and do things differently, he would have insisted that the communities negotiate agreements with CBG on how the land would be used and how it would be rehabilitated before mining started.

He urged leaders in the north to organize and prepare themselves to negotiate from a position of strength. “You need to document all of the impacts that you see. Take photos, write down what is said in meetings. Document everything,” Kounsa Baïlo Barry said.

The messages were taking hold. At the beginning of the first day of meetings, the northerners took turns standing up before the group to share their concerns and fears. The overwhelming sentiments were frustration and helplessness in the face of a powerful, opaque force. By the end of the last day, though, the tone had begun to change.

Ibrahima Diallo had come to the meeting, concerned about what might happen to the village that had drawn him back from city life in Senegal. In addition to being a farmer, he is a community development agent with the local commune government. This gives him a birds-eye view of what is coming, and what is at stake for the people living north of the river.

“CBG is coming to our villages and threatening us. They say the land is theirs and that we must accept this. They say if we object, they will send us to jail. But I’ve learned through this meeting that we have rights,” he said.

He continued: “We were like blind people before. But now because of what we’re learning, we have started to understand what is coming. We know that CBG wants to profit from our land. But we should also profit,” he said.

He added: “When CBG comes, we will be ready to stand up for our rights.”

When the meeting ended, Ibrahima Diallo and the others hopped on motorbikes and began the journey toward the Cogon River crossing, ready to take this message north to the people back home.

Expectations of Communities North of Cogon at Risk of CBG’s Mining Expansion Plans

Below is a summary of key expectations that emerged from discussions with members of the communities affected by CBG’s exploration activities north of the Cogon River during the research for this report.

This set of expectations was subsequently endorsed by the communities we visited during open village meetings. While these villages are only a small fraction of the total at-risk-communities who live inside the mining concession north of Cogon, Action Mines, ADREMGUI, CECIDE and Inclusive Development International believe meeting these expectations will avoid harm, conflict and costs in the future and result in better outcomes for all parties.

The communities’ expectations are as follows:

- Fully inform us about the extent of current exploration activities and potential future mining plans through village level meetings open to all community members.

- The census process must be fully transparent and all the losses we experience due to exploration activities, including loss of income, must be compensated fairly before any land taking or restrictions occur.

- If CBG and its shareholders wish to proceed with mining north of Cogon, they should engage us in a true dialogue process and only move forward with our consent.

- Before the start of any mining operations, all potential negative impacts on our communities and resources must be assessed in detail with our close involvement and participation.

- We should be provided with resources to have our own technical and legal advisers to support us in assessing risks and impacts, mapping our land and resources, exploring alternative ways in which mining can co‑exist with our livelihoods and developing proposals for the benefits our communities can receive.

- We should be given ample time to internally evaluate this information and make decisions about the terms and footprint of mining activities in our communities.

- Based on the findings of this participatory impact assessment, CBG should enter into formal negotiations with our communities and agree on plans to avoid or satisfactorily mitigate potential impacts on our water sources, land, livelihoods, and cultural heritage, and the benefits that we will receive in exchange for the exploitation of our customary land.

- CBG’s shareholders, lenders and companies that source bauxite from the mine should ensure that our rights are respected throughout mining operations and that we receive meaningful benefits based on our own development aspirations.

- Lenders should only agree to finance the mining operations in north of Cogon if CBG reaches an agreement with us on how mining should happen, including measures to minimize impacts on our resources and benefit-sharing to improve our living standards and of the future generations.

- Guinean authorities should take additional steps to protect the rights of the affected communities and ensure that economic development does not come at the expense of communities and environment.

Author: Dustin Roasa

Reviewers: Amadou Bah, Mariama Barry, Natalie Bugalski, Mohamed Lamine Diaby, Aboubacar Diallo, Nilsun Gursoy, Mignon Lamia, David Pred

Research: Mindie Bernard, Justine Franklin

Published by Inclusive Development International, Action Mines, ADREMGUI and CECIDE.

This publication was made possible with the generous support of Accountability Accelerator and 11th Hour Project.

This report is the first in a series that will look at how local communities around the world are impacted by projects connected to the renewable energy transition.