House engulfed by fire in Rakhine state in northern Myanmar during the genocide against the Rohingya. Photo redit: AFP via Getty Images

A joint publication of Inclusive Development International and ALTSEAN-Burma

3/09/2022

The $40 trillion environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment industry promises to align your money with your values – and make the world a better place. But an investigation by Inclusive Development International reveals that ESG-labeled funds have funneled billions into companies arming, funding and legitimizing the Myanmar military, the perpetrator of the Rohingya genocide and a violent crackdown on the country’s pro-democracy movement.

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military took control of the country in a coup, imprisoning much of the civilian leadership. In response, millions of people took to the streets throughout the country to march in support of democracy, defying threats of a crackdown.

The protestors were united in their opposition to military control. “We sang revolutionary songs. People wore body paint and made street art. It felt like a celebration,” said Thinzar Shunlei Yi, who worked as a community organizer before the coup. But as February wore on, security forces became more violent. “At some point, they started shooting water cannons at us. Then it was rubber bullets.”

On the last day of February, the situation turned deadly. Police and soldiers fired live rounds in a coordinated and ruthless operation targeting protestors. “They just kept killing us. We don’t know how many people we lost,” Thinzar said. Her friends were detained and tortured. She went into hiding and considers herself lucky to be alive.

At least 18 civilians, but probably far more, were killed that day. More than a year into the crackdown, the death toll has surpassed 2,500, according to independent estimates.

Crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Taunggyi, Myanmar in March 2021. Photo credit: R. Bociaga via Shutterstock

The military that has unleashed this reign of terror on the people of Myanmar is much more than a fighting force. It has been described as a state within a state, with its own parallel economy. It relies heavily on multinational corporations based outside of Myanmar for arms, equipment and funding – and to legitimize its brutal behavior to the international community.

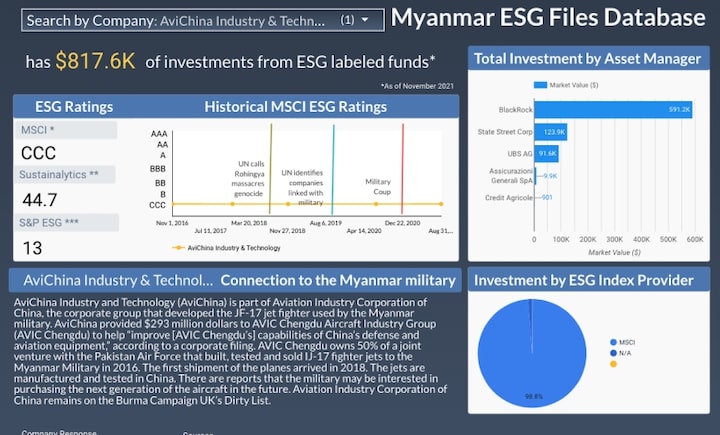

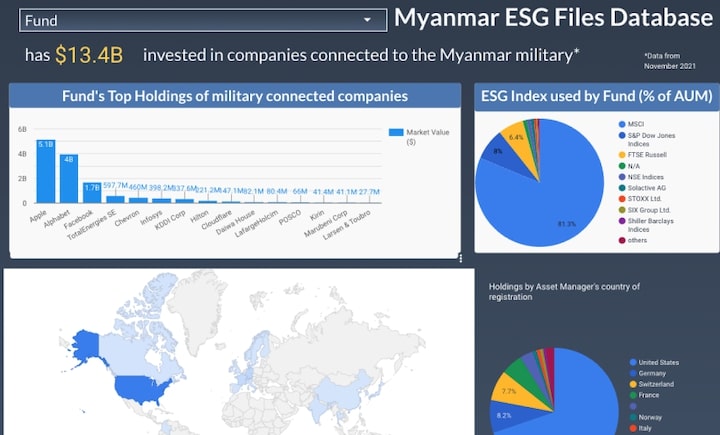

One year into the violent crackdown, Inclusive Development International has conducted an investigation of the junta’s corporate supporters to identify their major investors. The results of the investigation are shocking: A significant financial backer of these corporations is the environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing industry. Funds carrying the ESG label hold at least $13.4 billion worth of shares in 33 companies linked with the Myanmar military, the investigation has revealed.

Myanmar ESG Files Interactive Database

Inclusive Development International investigated hundreds of ESG-labeled funds, identifying 344 that have holdings in companies with economic ties to Myanmar’s military.

The Myanmar ESG Files Database allows users to access detailed information on each of these ESG funds and the companies they invest in. You can search the database by company to see information on each company’s ESG ratings and the funds that are invested in them, or search by fund to see more information on each fund’s holdings and the ESG indexes and ratings they rely on.

ESG funds are a rapidly growing subset of investing that claims to buy shares in environmentally and socially responsible companies. The $40 trillion industry promotes itself as a way for everyday investors – especially young people – to align their money with their values.

ESG’s rise has been fueled by a simple promise, repeated by industry executives and marketing materials aimed at the public. “Our mission [is] to help investors build better portfolios for a better world,” said Henry Fernandez, the CEO of MSCI, an index and ratings firm that is arguably the most important player in the ESG industry.

Despite these lofty promises, 344 ESG-labeled funds, managed by the largest investment firms in the world, hold shares in corporations that are enabling genocide and crimes against humanity in Myanmar. These companies include:

- Arms makers such as the Indian firm Bharat Electronics, which has supplied weapons, radar systems and communications technology to the Myanmar military, before and after the coup; and Elbit Systems, an Israeli defense company that has sold military-grade surveillance drones and parts to the military.

- Communications and technology companies such as Axiata Group of Malaysia, which has a network of mobile towers used by the military; and the U.S. tech firm Cloudflare, which provides website hosting services for the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs and the national police force.

- The U.S. social media platform Facebook, which played a “determining role” in fomenting hate speech that fueled the Rohingya genocide, according to the head of a UN fact-finding mission.

- Industrial conglomerates such as POSCO of South Korea, TotalEnergies of France and Chevron of the United States, which have generated billions of dollars in revenue for the military through joint ventures and other business relationships. (TotalEnergies and Chevron recently announced they will exit these ventures but have not yet done so.)

Facebook: “A Party to Genocide”

It is often said that Facebook is the internet in Myanmar. After the junta introduced democratic

reforms in 2011, millions of people installed the Facebook app on their phones, making it the

nation’s de facto gateway to the internet.

But with Facebook’s rise came warnings from human rights experts. The military and its

supporters were using the platform to spread hatred toward the Rohingya, a Muslim minority,

Facebook executives were repeatedly warned.

In August 2017, buoyed by this outpouring of hate, the military launched “clearance operations”

against Rohingya villages in western Myanmar, killing thousands and forcing more than 700,000

to flee to Bangladesh. The UN and 57 nations have called these operations genocide.

Facebook played a “determining role” in fomenting anti-Rohingya hate, according to Marzuki

Darusman, the head of a UN fact-finding mission to Myanmar. A former Facebook employee

turned whistleblower put it more bluntly: “I, working for Facebook, had been a party to

genocide.”

Facebook has admitted that it didn’t do enough to prevent its platform from being used to incite

violence. Yet even after the 2021 coup and the military’s violent crackdown on the

pro-democracy movement, Facebook continued to promote accounts that glorify the armed

forces.

The company’s algorithms have caused untold damage in other countries around the world,

numerous experts allege. Facebook is a danger “for children, for public safety, for democracy,”

Frances Haugen, another former employee, said in testimony to U.S. lawmakers.

Yet Facebook is one of the most popular stocks for ESG-labeled funds, which collectively hold

nearly $1.7 billion in the company’s shares, according to Inclusive Development International’s

research. MSCI and FTSE Russell are the leading ESG ratings and index providers underpinning

these investments.

“Facebook profited from our suffering,” Rohingya refugees allege in a $150 billion lawsuit filed

against the company in California. The same could be said for the ESG industry, which has

ignored years of evidence of Facebook’s role in genocide and crimes against humanity.

It is no secret that these 33 companies are helping to prop up a cruel military regime. The UN Human Rights Council, along with two civil society organizations, the Burma Campaign UK and Justice for Myanmar, have repeatedly and publicly exposed the companies’ business relationships with the junta.

Nor has the military’s participation in some of the most egregious human rights crimes of this century been a secret. Beginning in 2016, the military launched a campaign of massacres and ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya people in western Myanmar, sparking global headlines. Officials from the UN and 57 countries have labeled the military’s actions as genocide.

In the wake of the genocide, UN officials have called on businesses and investors to cut ties with the military. Human rights campaigners have echoed those calls.

Yet one year into the junta’s reign of terror and six years since its ethnic cleansing campaign, that ESG investment is still there. Perhaps most disturbing, 12 of the companies enabling the military have seen their ESG ratings – scores that gauge their environmental, social and governance performance, including on human rights – improve since the genocide and/or the coup.

Companies that benefit from ESG investment despite providing revenue or other support to Myanmar's military

Revenue

TotalEnergies SE

TotalEnergies SE Revenue $597, 697, 311 A Total is a joint-venture investor in the Yadana gas field, which since the coup has provided revenue to the military. In January 2022, after the ESG holdings data was collected, TotalEnergies announced it was exiting Myanmar.

Chevron

Chevron Revenue $460,044,646 BBB Chevron is a joint-venture investor in the Yadana gas field, which since the coup has provided revenue to the military. In January 2022, after the ESG holdings data was collected, Chevron announced it was exiting Myanmar.

Hilton

Hilton Revenue $221,210,080 A A Hilton-operated hotel is directly financing the military, according to leaked investment permits.

Daiwa House

Daiwa House Revenue $82,050,744 A A Daiwa House real estate joint venture in Yangon pays rent through intermediaries to the Quartermaster General, which finances arms and equipment purchases for the military.

LafargeHolcim

LafargeHolcim Revenue $80,381,909 A Through subsidiaries, LafargeHolcim has a commercial partnership with a military-owned company. In June 2020, LafargeHolcim announced that it would liquidate its Myanmar assets, but one year later Justice for Myanmar said the company was “dragging its feet” on the process.

POSCO

POSCO Revenue $65,997,996 BBB POSCO International, 51% owner of the Shwe Natural Gas Project, has had a profit-sharing agreement with the military-backed Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE).

Kirin

Kirin Revenue $41,407,740 A Kirin jointly owns Myanmar Brewery with a military-controlled company. Myanmar Brewery also provided financial support to the military for "clearance operations" against the Rohinga, according to the UN. Kirin said in February 2021 that it would end its partnership with the military but as of February 2022 had not yet done so.

Marubeni Corp

Marubeni Corp Revenue $41,071,421 A Marubeni is part of a joint-venture with a military-controlled company that is developing the Thilawa Special Economic Zone. Marubeni has also been involved in the development of the Shweli 3 dam in a conflict area of Northern Shan State.

COSCO Shipping Holdings

COSCO Shipping Holdings Revenue $22,195,191 B COSCO rents office space from the military-owned Myawaddy Bank Luxury Complex.

Adani Group

Adani Group Revenue $10,066,588 CCC An Adani Group subsidiary has paid $52 million to a military-owned company as part of plans to develop a port project in Yangon.

Tokyo Tatemono

Tokyo Tatemono Revenue $4,176,500 NA A Tokyo Tatemono real estate joint venture in Yangon pays rent through intermediaries to the Quartermaster General, which finances arms and equipment purchases for the military.

Siam Cement Group

Siam Cement Group Revenue $4,166,511 AA A Siam Cement Group subsidiary operates in an industrial zone owned by a military-controlled company.

PTT Exploration and Production

PTT Exploration and Production Revenue $2,107,000 A PTT Exploration and Production pays $500 million a year to a military-controlled energy company, according to Human Rights Watch. It is active in three of Myanmar's four major gas fields.

Yutong Bus

Yutong Bus Revenue $1,244,838 BBB Yutong Bus operates a bus manufacturing facility in the Inndagaw Industrial Complex, which is owned by a military-controlled company.

Olam International

Olam International Revenue $169,082 NA Olam International has purchased and exported rice for a military-owned conglomerate.

Lotte Corp

Lotte Corp Revenue $48,600 NA A Lotte subsidiary helped develop a hotel on land leased from the Myanmar military.

VPower Group

VPower Group Revenue $3,725 NA VPower helps operate a gas-fired thermal power plant as part of an agreement with a military-owned conglomerate.

Communications and technology

Apple

Apple Communications and technology $5,133,946,421 BBB Apple’s iOS store hosts apps that are essential to the operations of Mytel, a military-owned telecom company.

Alphabet

Alphabet Communications and technology $3,978,235,922 BBB Alphabet’s Google Play store hosts apps that are essential to the operations of Mytel, a military-owned telecom company.

Facebook

Facebook Communications and technology $1,695,233,396 B Facebook played a “determining role” in fomenting hate speech that fueled the Rohingya genocide, according to a UN official.

Infosys

Infosys Communications and technology $398,165,096 A An Infosys subsidiary provides digital banking services for Myawaddy Bank, a subsidiary of the military-controlled Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings.

Cloudflare

Cloudflare Communications and technology $147,079,828 BBB Cloudflare provides web services to Myanmar's military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs and police force.

Gilat Satellite Networks

Gilat Satellite Networks Communications and technology $74,541 NA Gilat has supplied satellite technology and services to the Myanmar military that Justice for Myanmar alleges may have aided in the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

KDDI Corp

KDDI Corp Communications and technology $337,560,595 AAA KDDI jointly operates the military-owned Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications, which collaborates with the regime’s surveillance program.

Sumitomo Corp

Sumitomo Corp Communications and technology $25,067,181 BBB Sumitomo Corporation jointly operates the military-owned Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications, which collaborates with the regime’s surveillance program. Sumitomo is also part of a joint-venture with a military-controlled company that is developing the Thilawa Special Economic Zone.

Axiata Group

Axiata Group Communications and technology $8,111,506 AA An Axiata Group subsidiary, which has a network of communications towers in Myanmar, does work for the phone network Mytel, which provides revenue to the military.

Weapons or equipment

Larsen & Toubro

Larsen & Toubro Weapons or equipment $27,716,499 BB Larsen & Toubro Ltd. helped adapt the Shyena torpedo, a lightweight missile, to be used by the Myanmar military, according to Burma Campaign UK.

Toshiba Corp

Toshiba Corp Weapons or equipment $20,947,246 BB A Toshiba subsidiary supplies turbines and generators for the controversial Upper Yeywa dam developed in part by a military-linked company. Military security forces protecting the project allegedly committed serious human rights violations including extrajudicial killings and torture.

Sinotruk

Sinotruk Weapons or equipment $5,720,353 BB Sinotruk vehicles are used by the military, including during the coup and crackdown on pro-democracy protests.

Bharat Electronics

Bharat Electronics Weapons or equipment $1,403,600 B Bharat Electronics has shipped radar components to the military, including after the coup.

Avic Aviation High-Technology Co Ltd

Avic Aviation High-Technology Co Ltd Weapons or equipment $842,799 NA AVIC has sold aircraft building materials to the defense weapons contractor AVIC Chengdu Aircraft Industrial Group. AVIC Chengdu built, tested and sold JF-17 fighter jets to the Myanmar military.

AviChina Industry & Technology

AviChina Industry & Technology Weapons or equipment $817,578 CCC AviChina Industry and Technology provided funding to AVIC Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group, which built, tested and sold JF-17 fighter jets to the Myanmar military.

Elbit Systems

Elbit Systems Weapons or equipment $241,835 A Elbit has sold military-grade drones and drone parts to the Myanmar military.

Company responses to Inclusive Development International’s requests for comment can be found here.

“The terrorist military junta is trying to control the people of Myanmar through extreme violence and inhuman acts. There is no question these investments are fueling that regime,” said the pro-democracy activist Thinzar.

Inclusive Development International’s investigation shows how the ESG industry is not, as it claims, directing investments to companies that make a positive impact on the world. It reveals how the industry has failed to respond to documented corporate human rights abuses and reflect them in its ratings and products sold as ESG.

Little-known yet powerful firms such as MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices – the highly profitable gatekeepers of hundreds of billions of dollars in ESG investment – are quietly greenwashing and directing capital marked as “ethical” or “sustainable” toward companies that are fueling gross human rights abuses.

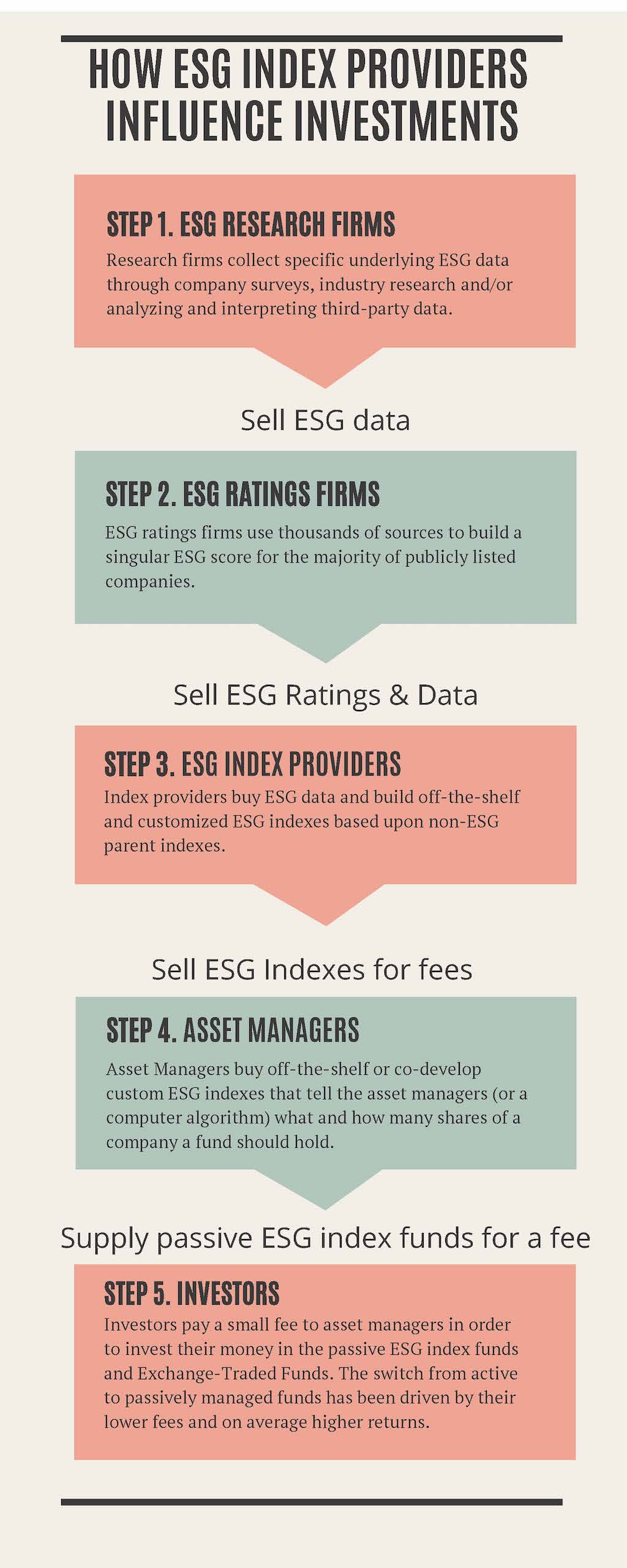

MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices construct lists – known as indexes – of companies they have rated highly on ESG factors, which greenlights them for ESG investment. Investment firms then use these indexes to create ESG funds that buy shares in companies that have been endorsed as responsible. These funds, which carry the ESG stamp of approval, are then made available to everyday investors.

Of the 344 ESG-labeled funds invested in companies linked to the Myanmar military, 69% are guided by ratings and indexes provided by MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices, the investigation revealed.

When members of the public invest in these ESG funds, they are led to believe they are putting money in companies that are environmentally and socially responsible, as the label and marketing suggest. But the reality is very different, due to numerous problems with how the ESG industry collects data, rates companies and constructs indexes and funds. Consumers may not understand that most ESG funds focus on how environmental and social factors affect a company’s share price, a concept known as “financial materiality,” rather than how a company’s behavior affects people and the planet.

“ESG is meaningless if companies included in ESG funds are in a business relationship or otherwise helping to fund a military which is responsible for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity,”

—Mark Farmaner, Director of Burma Campaign UK

In this way, the ESG industry is deceiving the public. Millions of private citizens, trusting the industry’s promises, have shifted their retirement savings from traditional funds to those carrying the ESG label. But instead of seeing their hard-earned savings invested in funds that address urgent challenges like the climate crisis or income inequality – or at least going to companies that are not causing harm – investors are unwittingly backing deeply irresponsible corporations, including some that are helping prop up one of the most brutal regimes of the 21st Century.

“ESG is meaningless if companies included in ESG funds are in a business relationship or otherwise helping to fund a military which is responsible for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity,” said Mark Farmaner, director of the Burma Campaign UK. “ESG funds must immediately divest from these companies if they want to maintain any credibility.”

“Duping the American Public”

In a very short amount of time, ESG investing has gone from niche to mainstream. With roots in the anti-Vietnam War and anti-Apartheid movements, socially responsible investing, as it was originally conceived, was championed as a way to carefully invest in only the most ethical companies. But this has morphed into the big business of ESG, which has been captured by Wall Street and has little in common with its forebearer.

Because ESG has never really been defined, either by financial regulators or the industry itself, it has come to mean different things to different people. Some say it is the future of investing. Others say it will help save the planet. For some of the most powerful players in the industry, ESG has nothing to do with ethics at all. Rather, it is about “financial materiality,” another set of factors for investors to consider when trying to maximize their returns.

Firms like MSCI, which are driving the industry’s growth, have publicly said some version of all three, tailoring their message to the audience. Matt Moscardi, who worked at MSCI for nearly 10 years, recently wrote on an influential responsible investing news site that this lack of standardization should be celebrated – and that regulators should keep their hands off ESG – because the free-for-all is exciting. This ambiguity has also been good for business.

Pro-democracy activist Thinzar Shunlei Yi in Yangon, Myanmar. Photo courtesy of Thinzar Shunlei Yi.

Studies have found that members of the public, in particular people ages 25-40, want to make a positive impact on the world with their investments. With young people set to receive trillions of dollars in wealth from their aging parents, in what is expected to be the largest asset transfer in history, investment firms will be vying for their business with numerous products that carry the “ESG” or “sustainable” label.

Yet the public doesn’t really understand what ESG is, according to multiple surveys. The ESG industry has filled this vacuum with marketing materials and commentary aimed at capturing investors with a conscience.

MSCI’s website promotes its ESG products as a way to “support positive social or environmental benefits” and ensure that investing is in “alignment with an organization or individual’s moral values and beliefs.” Other firms that sell ESG products, such as the large asset manager Vanguard and the investing app Acorns, make similar claims. Advertisements for ESG funds often feature sepia-toned images of human hands carefully nurturing tree saplings to convey a sense of environmental and social stewardship.

Increasingly, employment-based 401(k) plans and other retirement accounts, investing apps like Acorns and Robinhood, and major pension funds like TIAA and ABP are offering ESG options. Even the staff pension fund for the UN, which manages the retirement savings of thousands of employees across its agencies, uses MSCI’s ESG indexes to guide its investments. (As a result, UN employees may hold shares in the very companies that its human rights experts say are equipping and funding the military in Myanmar. The UN pension fund did not respond to requests for comment.)

What are the Human Rights Responsibilities of ESG Firms?

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights call upon all companies to prevent or address human rights impacts “that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships.” This includes indirect relationships that a company may have through multiple intermediaries throughout its value chain. Where a business relationship exists, the company must use whatever leverage it has over the entities causing or contributing to human rights abuses in order to address those abuses.

The ESG firms that score companies and include them on ESG-labeled indexes have a business relationship with those companies. This is because the corporations that ESG firms rate and list on their indexes are an essential component of the products and services that they are selling, and are therefore an integral part of their value chain. When they assign high enough ratings and include these companies on their ESG-labeled indexes, they facilitate the flow of investment to those companies, and they earn profits themselves for providing that service to investors. Companies also directly provide information on their ESG policies and practices to the ratings firms in an effort to receive reputational and financial benefit from these firms. Therefore, when companies that have contributed to human rights abuses are included on ESG-labelled indexes, the index providers are directly linked to those abuses.

This multifaceted business relationship creates a human rights responsibility for ratings firms and index providers (often part of the same corporate group) to use their considerable leverage with those companies to address the human rights abuses that they are linked to, including by downgrading their ratings and excluding them from their ESG indexes when they fail to act.

More and more investors, hoping to make a positive impact on the world with their money, are trusting the industry’s promises and choosing the ESG option. Some $40 trillion of professionally managed assets globally consider ESG factors. That is on track to exceed $53 trillion by 2025. With fees for ESG funds typically higher than conventional funds, consumers have been willing to pay a premium for these products.

This has been very good for the bottom lines of MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices, the big three ESG ratings and index firms. MSCI, the largest player, estimates that $1 trillion of assets under management globally are tied to its indexes. MSCI’s average share price in 2021 was $535, giving MSCI itself a market valuation approaching $40 billion. These are extraordinary numbers for a research firm with approximately 4,000 employees.

The industry’s growth has attracted the attention of financial regulators. The European Commission has begun issuing regulations that define what terms like “green” and “sustainable” mean when applied to investment products. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which lags behind European regulators, has formed a task force to investigate potential ESG misconduct. Observers expect the SEC to follow Europe’s lead and begin issuing rules that define labels like ESG. But given the size of the industry, and its systemic and manifest flaws, regulators face a steep challenge.

It remains to be seen whether regulators can reconcile ESG’s fundamental contradiction: Consumers have been told that when they invest in an ESG fund, they are buying shares in companies that are making a positive impact on the world – or, at minimum, not causing people and the environment harm. The industry, on the other hand, views things entirely differently. To many insiders, ESG is a way of insulating investors from the financial – not moral – risks of companies that cause harm.

This disconnect between how ESG is packaged and marketed, as an initiative grounded in ethics, and how it actually operates, as a morally neutral set of risk assessments designed to maximize investor returns, is at the heart of the ESG deception being foisted on the public.

In principle, it is no different from a pair of jeans carrying the Fair Trade label that was manufactured with slave labor, or apples labeled as “organic” that are grown with industrial chemicals.

This disconnect between how ESG is packaged and marketed, as an initiative grounded in ethics, and how it actually operates, as a morally neutral set of risk assessments designed to maximize investor returns, is at the heart of the ESG deception being foisted on the public.

Tariq Fancy, the former head of sustainable investing at BlackRock, made waves in early 2021 when he became the highest-profile insider to blow the whistle on ESG. “The financial services industry is duping the American public with its pro-environment, sustainable investing practices,” Fancy wrote in a USA Today column. He said the industry is doing “irreversible harm by stalling and greenwashing… all in the name of profits.”

As a key architect of this deception at BlackRock, Fancy saw its inner workings up close. Yet it doesn’t take an insider to know that ESG is fraudulent. A closer look at publicly available information on how the ESG industry operates – and how the worst corporate abusers end up in ESG funds – offers an indictment that is sufficiently damning.

How ESG Funds are Made

For an industry ostensibly built on measuring the environmental and social performance of companies, ESG fund managers have been remarkably comfortable outsourcing the work of due diligence to a constellation of third parties. They are arrayed into four basic levels that make up the ESG decision-making chain.

At the top of that chain are the research firms. These firms collect information on how companies perform in the world – and how they say they perform – using a variety of sources. This includes company self-reporting such as marketing materials and regulatory filings. It also includes independent sources like the news media, NGOs and industry analysts.

The research firms rely heavily on artificial intelligence and big data tools to trawl through large volumes of information online and collect the relevant pieces. However, these tools don’t capture human rights abuses that are not covered by the news media, NGO reports or other publications, a particular problem in countries with repressive political environments or without a vocal civil society. In these cases, the only information available about a company may be its website and environmental and social policies, which of course portray the company in a favorable light.

The research firms then sell this often-incomplete information to the next level of the value chain, the ESG ratings firms, which rate companies on their ESG performance. These firms funnel that information into proprietary computer models that crunch raw data on a range of complex and disparate issues – from gender equity on boards to commitments to reduce water use – and reduce them to environmental, social and governance scores for each company.

These separate scores are then consolidated into a single, overarching ESG score which forms the basis of how the industry views a company. This overall score is the single most important factor in determining whether that company is included in ESG funds and attracts capital that is considered “sustainable.”

The firms develop their ratings methodologies in-house. Consequently, they are treated as commercial secrets, insulating them from public and regulatory scrutiny. Because there are so many different approaches to ratings, the ESG scores of a single company can vary wildly across the ratings firms.

For instance, a company like Larsen & Toubro, an Indian firm that supplies weapons to the Myanmar military, is rated a respectable score of BB by MSCI, but a much worse High Risk by major ratings firm Sustainalytics. Meanwhile, the U.S. oil giant Chevron, which in addition to pumping revenue into the Myanmar military is also the second-largest corporate driver of climate change, gets a good BBB from MSCI, but a Severe Risk rating from Sustainalytics.

Such divergences would never appear – nor be tolerated – in the highly regulated credit ratings industry, where firms like Moody’s and Fitch score companies on their ability to pay back debt. Yet these discrepancies persist in ESG.

Nor is it clear how significantly human rights abuses impact a company’s overall ESG score. This is by design. As mentioned, most ratings firms focus on financial materiality, which is a way of assessing how ESG risk factors might affect a company’s financial performance. For example, if a company colluded with security forces to violently displace local families from their homes and farms in a country in West Africa, that would likely only affect the company’s ESG score if it presented a risk to its share price.

Given this, a corporation that commits serious human rights abuses in countries where legal accountability is weak may not face financial consequences, such as lawsuits or regulatory violations, that could affect its ESG score.

Flood-affected area after an auxiliary dam in the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy hydropower complex collapsed in rural Champasak Province in southern Laos. Photo credit: Roeungrit Kongmuang

Even if human rights abuses are material enough to impact an ESG score, companies have ways to compensate. Making a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or adopting new data protection measures can help companies burnish their ESG scores and counteract problems in other areas, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek investigation.

There are many examples of this among the worst corporate abusers. For instance, the Korean construction company SK Group, alleged to have caused a deadly dam collapse in rural Laos in 2018, has seen its MSCI ESG rating increase twice, from BBB to AA, since the disaster. SK Group appears to have compensated for the reputational damage caused by the collapse by rebranding itself as an eco-friendly company committed to renewable energy projects. While thousands of victims of the Laos dam disaster have yet to be adequately compensated and are languishing in squalid displacement camps, SK Group has reaped the rewards of a stellar ESG reputation.

The French oil major TotalEnergies is building the world’s longest heated crude pipeline across East Africa in order to open new oil fields in Uganda’s Albertine Rift. The pipeline and oil fields are predicted to impact the land of more than 100,000 people, threaten critical ecosystems, and jeopardize an essential fresh water source for over 40 million people. Yet TotalEnergies gets an A rating, the third- highest, from MSCI and is considered an industry leader on carbon emissions, despite fossil fuels being central to its business model.

The ratings firms sell these frequently flawed ESG scores to the next layer in the value chain, the index providers. This layer is crucial because it is where data on companies is converted from something abstract into financial products called indexes, which determine where ESG capital is invested.

Index providers typically begin the process with a conventional index, which is a list of companies whose performance is designed to track, say, a national economy or a particular industry. The most famous examples are the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average, non-ESG indexes made up of large corporations that are publicly traded in the United States.

In order to create an ESG index, companies on the conventional index that fall below a certain ESG ratings threshold are removed from consideration for the ESG index. The remaining companies with high enough scores are placed in the ESG index. The index provider then “weights” each company, meaning it allocates each one a certain percentage of the ESG index’s total investment value. This weighting system tells fund managers how much money to invest in each company.

For the large index providers like MSCI and S&P Dow Jones Indices, weighting is based not on a company’s ESG performance, as a reasonable person might assume, but on its market capitalization, a rough approximation of its size. In other words, being large and valuable – as opposed to getting high ESG ratings – is the key factor in determining how much investment a particular company receives.

The index providers then sell these ESG indexes to investment firms and pension funds, which use them as guides to construct funds that carry the “ESG” or “sustainable” label. For ESG funds that are passively managed, the fund manager will follow the index more or less exactly, making few, if any, deviations. Active fund managers, who have wide discretion to pick stocks, may deviate, but the index is nonetheless the starting point, the investible universe.

Historically, actively managed ESG funds have dwarfed their passively managed counterparts. But the trend is reversing: In 2020, 70% of ESG capital went to passively managed funds, a shift that is expected to continue. The growth of passively managed ESG funds will place even more power in the hands of the index providers, because they are fully in charge of creating fund portfolios.

2020 Net Flows into ESG funds

Passive vs. Active

70%

Passive Funds

Active Funds

Another trend that is concentrating power in the hands of index providers is vertical integration. The big three index providers – MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices and FTSE Russell – have in recent years begun producing their own ESG ratings. As they and other index providers take control of this ratings function, they exercise even more control over the process.

All of this makes MSCI, S&P Dow Jones Indices and FTSE Russell the most important, but probably least understood, players in the ESG ecosystem. As the key deciders of what companies appear on the largest, most popular ESG indexes, they wield immense power over capital marketed as responsible. This gives them extraordinary leverage, including over companies that cause or contribute to human rights abuses. Under international human rights standards, they have a responsibility to use that leverage to prevent abuses and remediate harms. Yet they almost never do.

“Accessories to Murder”

In April 2021, S&P Dow Jones Indices made an extraordinary announcement: It was removing Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone, India’s largest port operator, from its prestigious Dow Jones Sustainability Indices. The move was triggered by “heightened risks to the company regarding their commercial relationship with Myanmar’s military, who are alleged to have committed serious human rights abuses under international law,” the index provider said in a statement.

The human rights concerns highlighted by critics of Adani Ports were serious. The UN had exposed Adani Ports’ plans to build a shipping container terminal on land leased from a Myanmar military-controlled company. Following the coup, Adani Ports reportedly paid more than $100 million to that military company, providing significant revenue that the junta could use in its ongoing crackdown.

Campaigners have on occasion called for the removal of other companies from ESG indexes due to human rights concerns. Other companies have been put on the watchlists of ESG indexes, due to changes in their ESG ratings caused by cumulative human rights concerns. But Adani Ports was unique: An index provider had removed a company because of specific human rights allegations in one country, without waiting for a change in the company’s ESG rating to trigger the removal.

The removal was a major hit for Adani Ports’ carefully constructed, and relatively new, reputation for sustainability. In November 2020, before the military coup in Myanmar, when Adani Ports had made it onto the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices, the company celebrated the decision with a press release. Its CEO, Karan Adani, called it a “shot in the arm” that showed the company was “on the right path” in its “ambitious” sustainability journey.

Five months later, when S&P Dow Jones kicked it off, Adani Ports saw its share price plummet nearly 10%. Mired in controversy – and worried about U.S. sanctions – Adani Ports relented and announced it would scrap the project and end its involvement in Myanmar. The episode showed that when an index provider meets its human rights responsibilities and exercises its considerable leverage to address serious concerns, it can help cut off a significant source of revenue for a brutal military regime.

“How can it be that responsible investment funds hold shares in companies that are funding and equipping the military? That makes these funds accessories to murder.”

—Mulan, a pro democracy activist in Myanmar

All companies have a responsibility to exercise leverage, whenever they have it, to prevent or address human rights violations under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. These authoritative global standards, endorsed unanimously by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011, apply to businesses in all sectors, including financial services.

The power of index providers to control the flow of global capital is enormous, and for companies seeking to attract some of the growing pot of ESG investment, index providers have immense leverage. They can determine whether a company needs to address human rights abuses in order to make it into or remain on their indexes, and consequently attract, or lose access to, a significant and growing portion of the capital markets. Under the UN Guiding Principles, as well as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, index providers must exercise this leverage to prevent or address the human rights impacts they are linked to through their business relationships.

Yet despite taking action on Adani Ports, S&P Dow Jones Indices has not taken similar action against other companies providing support to the Myanmar military. In written responses to questions from Inclusive Development International, the firm emphasized that its ESG indexes are strictly rules-based. It said that other companies with ties to the military did not meet its threshold for exclusion, without providing more detail.

“To assess the severity of a given issue, the S&P Global ESG Research team assesses the magnitude of the case, in terms of the economic, social or environmental impact (or a combination of) and the overall response to the issues by a company,” a representative wrote.

FTSE Russell, one of S&P Dow Jones’ chief competitors, recently published a research paper which argues that rules-based ESG indexes are themselves the way index providers exercise leverage – not just for themselves but also for the passive investors who rely on indexes.

In a written response to Inclusive Development International’s questions, a FTSE representative explained: “Our key finding is that if companies have clarity on how they can meet the index inclusion rules, or increase their weighting in the index, then they can be incentivized and rewarded to achieve real-world improvements in corporate sustainability performance.”

Yet the only way a constituent company can be removed from the FTSE4Good index, aside from its ESG rating falling below the required thresholds, is if FTSE Russell’s monitoring of the news media for global controversies finds that the company breached a threshold level “that equates to the most extreme ESG controversies,” a term that is not defined in the index provider’s published rules, but which implies a very high bar.

MSCI has taken similar pains to emphasize that its ESG indexes are rules-bound. Once MSCI includes a company on an ESG index, only the highest-profile, most financially risky scandals – those getting the worst score, zero, on a 10-point scale MSCI uses to gauge controversies – are removed.

When asked about Myanmar, MSCI representatives told Inclusive Development International that its controversies team had reviewed the UN’s 2019 fact-finding report on companies doing business with the military.

Yet MSCI had decided that none of the companies, including Adani Ports, were worthy of the lowest controversy rating necessary for removal from its indexes, despite their exposure to genocide and crimes against humanity, in an apparent dismissal of the conclusions reached by UN human rights experts.

MSCI representatives acknowledge that the firm has leverage over companies on its ESG indexes. “Companies often come to us asking what they need to do to stay on an ESG index,” a representative said. MSCI also does not dispute that it has human rights responsibilities.

Yet MSCI had decided that none of the companies, including Adani Ports, were worthy of the lowest controversy rating necessary for removal from its indexes, despite their exposure to genocide and crimes against humanity, in an apparent dismissal of the conclusions reached by UN human rights experts.

But because MSCI fashions itself as a research firm that is constrained by rules that are narrowly pegged to financial materiality – even though MSCI created those rules – it has managed to distance itself from the profoundly negative implications its decisions have for investors, entire countries and the future of the planet. Perhaps most perversely, MSCI has not only refused to address those problems, it has told the public that it is part of the solution.

This is especially confounding for pro-democracy activists in Myanmar, who are fighting a battle for their country’s future against a ruthless dictatorship. “Everyone knows the military is using weapons and technology to kill civilians,” said a campaigner who goes by the name Mulan. “How can it be that responsible investment funds hold shares in companies that are funding and equipping the military? That makes these funds accessories to murder.”

Members of the Rohingya Muslim minority take shelter in a no-man’s land between Bangladesh and Myanmar during the 2017 genocide. Photo credit: K. M. ASAD / AFP via Getty Images

This, in sum, is the crisis facing ESG. As people harmed by these investments begin to speak out, as investors with a conscience learn how their money is being used, and as financial regulators move in to scrutinize the industry’s operations, it will become clear that ESG is a false solution that undermines the movement for genuine socially responsible investment and corporate accountability.

Socially responsible investing, as originally conceived, can still be a force for good and a driver of corporate respect for human rights. But short of a complete overhaul – and a commitment by key players to take human rights seriously, divorced from any consideration of financial materiality – ESG will remain a dangerous distraction from that vital goal and just another fraudulent greenwashing scheme being sold to the public.