China Global Newsletter | Edition 11: September 2025

The Second Trump Administration and Chinese Overseas Investment and Trade

Since Donald Trump’s inauguration, his administration has issued a flurry of executive orders and policies with far-reaching consequences. This edition of the newsletter explores the potential impacts of these changes, particularly for China’s overseas footprint, and asks what they mean for the broader path toward sustainable development.

President Trump Signs Executive Orders in the Oval Office. Source: White House.

Trump 2.0 Policy Whirlwind

In his second term, President Trump moved quickly to undo regulations and orders issued by the previous administration. Alongside these policy changes, the administration set about rapidly implementing huge cuts to government programs. One of the most drastic moves was to effectively dismantle the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), leaving vital humanitarian and development projects around the world without funding and effectively erasing one of the United States’ most visible soft power tools.

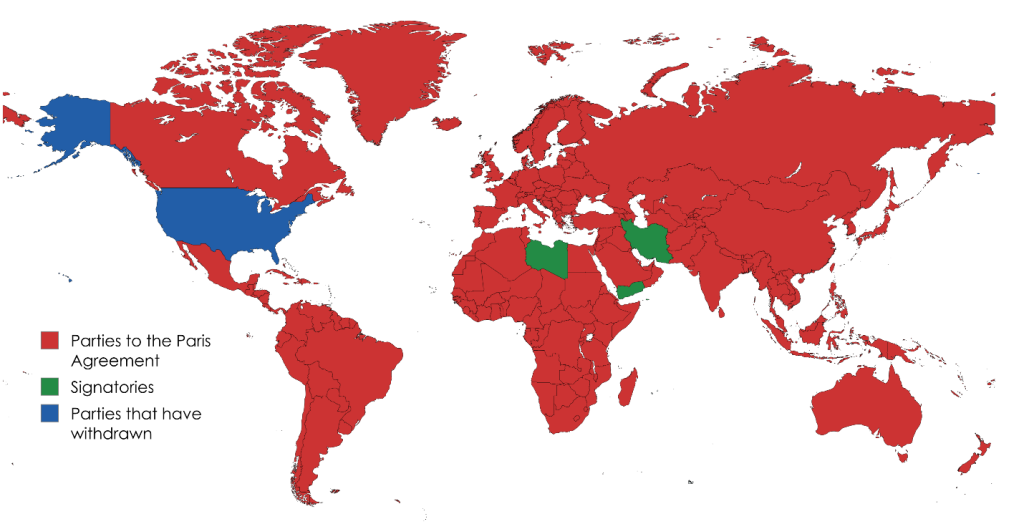

The United States also stepped back from its multilateral commitments, slashing funding to United Nations agencies and other multilateral initiatives, and withdrawing from the World Health Organization and the Paris Climate Agreement. These shifts have weakened international frameworks that underpin accountability and human rights protections in development contexts.

Pallets of food, water and supplies on a runway in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Source: USAID.

Global Trade Norms Upended

On April 2, 2025, Trump announced sweeping new tariffs affecting nearly every country and causing massive disruptions in global trade and financial markets.

Trump’s use of tariffs to strengthen the U.S. position in trade negotiations and to reduce trade deficits is not new—he introduced a range of tariffs during his first term, including tariffs focused on China, which led to retaliatory measures by the Chinese government—but this escalated dramatically in 2025.

In April, Trump announced new tariffs targeting almost every other country, causing stock and bond markets across the world to temporarily crash. U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods reached 145%, leading China to impose a 125% tariff in response. These and other tariffs have since been relaxed, but the situation remains unpredictable, leaving many countries reckoning with how new tariffs or an expanded U.S.-China trade war could impact them.

Southeast Asian nations are watching closely. While Chinese companies have been offshoring manufacturing to Southeast Asia for close to two decades, this accelerated during Trump’s first term, as Chinese firms looked to sidestep the new tariffs. The recent imposition, and ongoing threat, of high tariffs targeting key manufacturing countries such as Vietnam will hamper this movement and threaten the economies of countries that have become heavily dependent on exporting manufactured goods to the United States. This includes Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Cambodia, which may now find themselves pressured to agree to trade deals and other concessions with the United States that are less favorable to China.

Elsewhere, the Trump administration is leveraging trade pressure to compel the EU to ease its corporate sustainability rules for U.S. firms. Under a recent U.S.–EU trade framework agreement, secured under threat of heavy U.S. tariffs, the EU pledged to ensure the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) “do not pose undue restrictions on transatlantic trade.” It also pledged to “work to address the concerns of US producers and exporters regarding the EU Deforestation Regulation, with a view to avoiding undue impact on US-EU trade,” and to provide “additional flexibilities” in the implementation of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for U.S. companies.

This apparent shift in EU policy from setting global sustainability benchmarks to negotiating trade-driven exceptions with the U.S. government sets a dangerous precedent. It is also likely to heighten China’s unease over the EU’s expanding environmental and human rights due diligence rules, which it already argues effectively serve as disguised restrictions on Chinese companies, in addition to creating excessive bureaucracy, raising compliance costs, and disrupting trade.

Cargo terminal in global trade hub Singapore. Source: chuttersnap.

Shifts in Promoting Responsible Overseas Business

The previous U.S. administrations’ efforts to incentivize U.S. companies to invest in overseas renewable energy and sustainable transition projects, and to support governments, academia and civil society around the world, made important contributions to steering development towards a more climate-friendly path. The Trump administration has taken hostile actions toward sustainability and corporate accountability, both at home and abroad, threatening to scrap climate disclosure rules and abandoning proposed rules regarding ESG reporting mandates.

This rapid shift, led by the world’s largest economy, has raised concerns of a race to the bottom in global sustainability standards. As China seeks greater leadership on the international stage, the question remains: will it uphold its pledges to green the Belt and Road Initiative, or follow the United States in backsliding?

Chinese companies and banks have been, and continue to be, connected to high-risk and controversial projects, but important developments have occurred over the past decade. While economic factors remain at the forefront of project risk assessments, local discontent and criticism regarding projects that have caused environmental and social harms are playing an increasingly important role in project decisions. Although significant gaps remain in terms of hard regulation of overseas projects’ environmental and social management, the Chinese government has adopted a broad range of policies and guidelines that reflect the state’s increased attention to the issue and its expectations for Chinese companies and banks involved in overseas projects (see our earlier newsletter for more on this). China’s commitment to cease building new overseas coal plants, and the fact that new overseas energy finance has now shifted toward non-fossil projects, are also important moves.

International support and collaboration have played an important role in this progress. For instance, the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC) worked with the OECD to develop the Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains, explicitly modeled after the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (see our publication on the guidelines here). Although the guidelines remain untested, they present a step in the right direction. If we continue to see a retreat from global sustainability commitments, such international cooperation will become more critical than ever.

Global projects will continue to be a priority for China, and will continue to entail risks, but there have been promising signs and now a sustained rhetorical emphasis on not just delivering projects, but ensuring they are of high quality and support local people’s needs. The requirements for feasibility and impact studies, if implemented well, could help project developers and financial institutions to better identify risks that must be addressed, including economic and political risk, but also environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns.

Often, we can only speculate on the reasons why a project may be dropped or altered, but there are some encouraging signs that some Chinese companies and financial institutions are following the policy trend and acting more cautiously overseas. Risk tolerance may not be as high as it once was.

However, improving public communication about involvement in, or withdrawal from, projects is a key element in achieving commitments to ‘green’ overseas projects. Enhancing transparency around projects, including proactive communication with the public, affected people, and civil society will help to clarify the extent to which sustainability considerations are impacting decisions around investment. This will not only make such decision by Chinese stakeholders more impactful, but also help build a more accurate perception of Chinese overseas investment in this new phase.

Rolling Back Climate and Sustainability Commitments

The United States has significantly rolled back its climate and sustainability commitments, withdrawing from the Paris Agreement (citing the burden it places on the American economy) and signing the “Unleashing American Energy,” executive order, which rolled back Biden-era climate policies and set new priorities including encouraging oil and gas exploration, reducing regulatory barriers and removing targets for electric vehicle adoption. The administration has also cut funding and cancelled programs that would have contributed to global energy transition projects.

Cuts to foreign assistance programs more broadly will also have wide-ranging impacts. The sudden withdrawal of funding has already affected civil society groups and academic institutions that research and document the impact of development projects, groups that advocate for more sustainable finance and investment, journalists reporting on these issues and the stories of the people impacted, as well as other governments’ investments in climate resilience and energy transition projects.

In addition to their important implications for global climate and sustainable development efforts, the United States’ policy changes and aid rollbacks raise the question of who or what will take its place.

Will China Step into the Gap?

All of this raises the question of how gaps left by the U.S. withdrawal can be filled. Various observers have suggested these policy shifts will diminish U.S. global influence, allowing China to capitalize on the moment to strengthen bilateral ties and play a stronger role in multilateral institutions.

Given the substantial difference between Chinese and U.S. foreign aid, in terms of scale, type and delivery mechanisms, China is unlikely to fill the gap without fundamentally overhauling its approach to development assistance. China’s foreign aid has consistently amounted to only a small share of that provided by the United States. In 2024, for example, the United States provided $63.3 billion in official development aid, maintaining its position as the world’s largest donor, while China’s total foreign aid budget was estimated to be $2.85 billion for the same year.

It is unlikely that China will drastically increase aid spending to fill the void. If it does, it will not provide the same type of support that the United States has. U.S. aid is primarily grant-based, with a focus on governance and humanitarian assistance. By contrast, Chinese assistance is dominated by loans—particularly concessional loans—channeled into large infrastructure and production projects, typically with substantial involvement from Chinese firms. The recipients also differ: Chinese aid is negotiated bilaterally through government-to-government agreements, while U.S. aid often bypasses governments, flowing directly to non-state actors such as civil society groups.

In the realm of climate and energy transition policy and related trade, there are more obvious areas where China could take on a more central role. Although it remains a major carbon emitter, China has sought to position itself as a leader in global climate policy, and it is a front-runner in the investment and rollout of clean energy technology. Its push into renewables has been driven both by necessity and commercial interests. Should U.S. support for renewable energy investment and innovation continue to wane as the Trump regime prioritizes fossil fuels, Chinese firms could grow increasingly dominant. On the other hand, should the trade war continue and intensify, impacts on supply chains and movement of goods could hamper Chinese firms invested in this sector, while also damaging the economies in which Chinese firms have become embedded.

It is possible that in response to new tariffs imposed by the United States, countries with export-oriented renewable energy industries will reposition to focus on domestic and regional markets. For years, Chinese firms have been relocating production of solar panels to Southeast Asia, and in April the Trump administration levied tariffs as high as 3,500% on solar panels produced in the region. Even if these tariffs do not stick, exporters might opt to hedge against the potential volatility they would bring by focusing on domestic and regional markets, where there is strong and often untapped potential for the rollout of solar. This, in turn, would reduce pressure to invest in new fossil fuel power generation projects to meet growing energy needs.

The United States’ withdrawal from programs established to support an energy transition may mean gaps are filled by others, including China. Should this be the case, there is both opportunity and imperative for China to further strengthen policies related to overseas projects, ensuring that projects are not just green, but that they are genuinely supported by and beneficial for local people.

Looking beyond the narrow prism of U.S.–China rivalry, the gulf between development needs and available resources was already vast before Washington’s deep aid cuts, and progress toward finding a sustainable path far too slow. No single actor can solve these challenges alone. The real question, in the wake of a U.S. retreat, is whether the rest of the world can hold together to resist being pulled into a spiral of regulatory backsliding, a global race to the bottom, and the geopolitical cynicism that threatens to erode collective efforts needed to build a sustainable, inclusive and just world.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletter and subscribe to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published here.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong. The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.