China Global Newsletter | Edition 5: December 2021

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

In 2013, China announced that it planned to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). This was followed by intense speculation around which countries would join, how closely the new institution would follow the path set by already established multilateral development banks, and what role China would play in its governance. Human rights advocates and environmentalists in particular were concerned that gains made in advocating for accountability in development finance over the past decades would be undermined by the AIIB, generating a new race to the bottom in social and environmental standards.

Initially at least the AIIB has taken a relatively cautious path. It commenced by largely co-financing projects with other multilateral development banks, applying their standards and grievance mechanisms, and invested in traditional infrastructure projects such as roads, power plants and transmission. As the bank got into its stride, it began developing its policies and strategies and building a more complex portfolio. This edition of the China Global Newsletter takes stock of the bank, looking at where it stands six years on from its establishment. It covers:

Putting the AIIB in Context

After its establishment in 2015, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) adopted a bold agenda to create a “lean, clean and green” multilateral development bank for the 21st century. It soon set about developing the structures, staffing and policies required to achieve this vision.

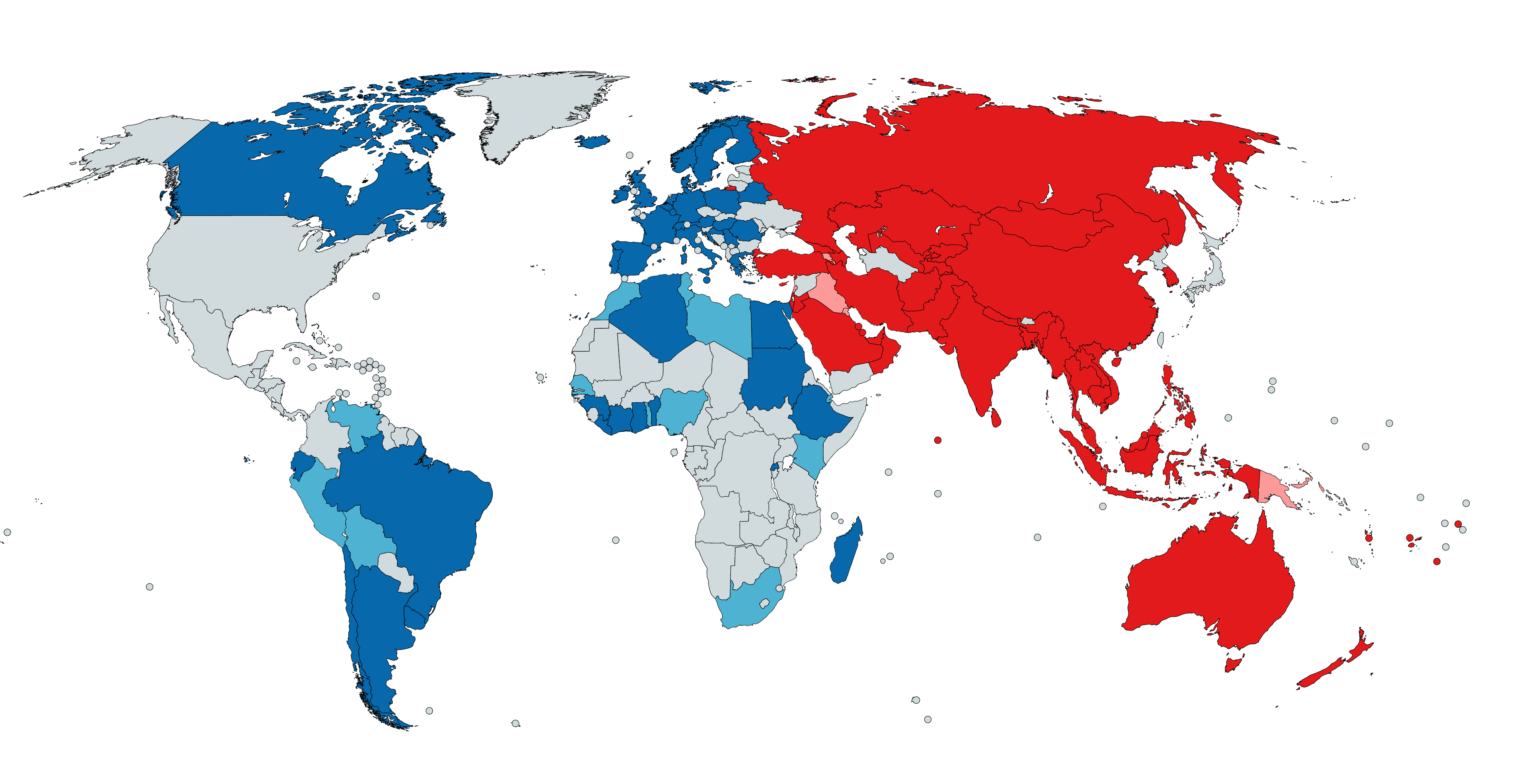

Some five and a half years after approving its first project in June 2016, the bank has built a considerable portfolio of 151 projects worth almost US$30 billion as of November 2021. Its membership has swelled from the 57 founding members to more than 100 countries, expanding beyond Asia to include most EU countries, Australia, Canada, and others from Latin America and Africa.

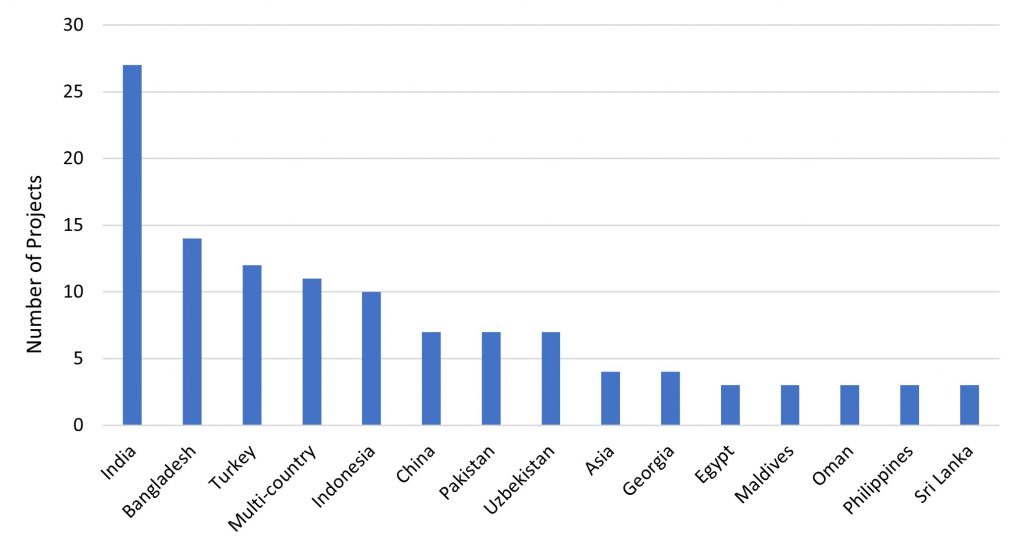

India is by far the top recipient of AIIB loans, accounting for almost 20% of the bank’s projects. The bank has projects in 32 countries, but the top three recipients, India, Bangladesh and Turkey account for more than a third of all approved projects.

Geography of AIIB Projects (top 15 destinations)

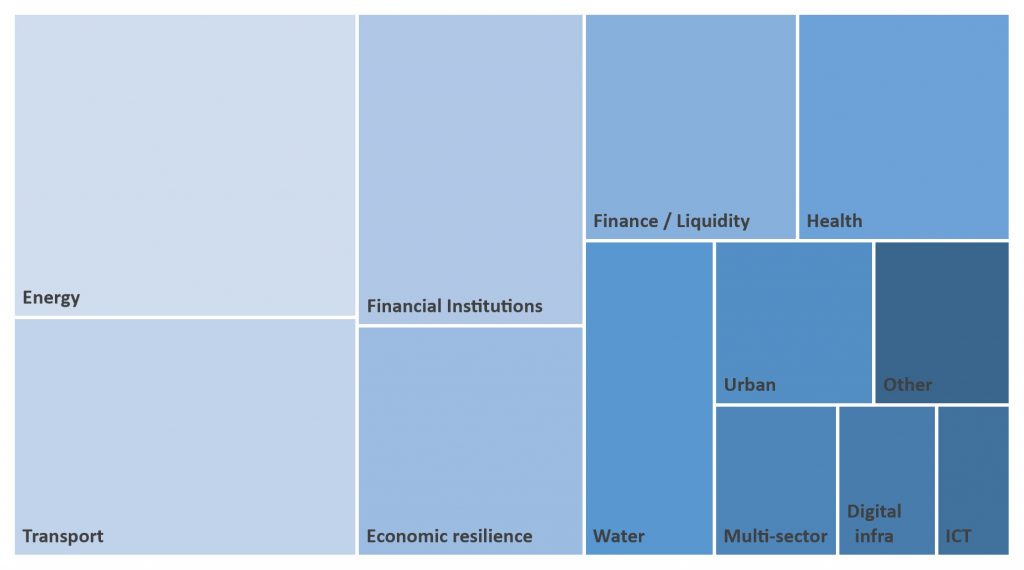

Energy projects are the top recipient of AIIB financing, followed by transport and then financial institutions (mostly banks and equity funds targeting various types of infrastructure). After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the bank set up a Crisis Recovery Facility and rapidly deployed funds for healthcare, economic resilience and liquidity, mostly co-financed with other multilateral banks. If these projects are removed, energy, transport and financial institutions represent almost two thirds of the bank’s entire portfolio, in keeping with its focus on infrastructure.

Sectoral Breakdown of AIIB Portfolio

There has been much discussion around China’s role and influence in the establishment and direction of the bank. China has by far the largest stake in the AIIB, which is headquartered in Beijing and led by President Jin Liqun, who has worked for China’s finance ministry, central bank, and sovereign wealth fund, as well as serving as a vice president at the Asian Development Bank. Holding almost 31% of the bank’s shares, China has a voting share of over 26.5%, meaning it has a powerful voice in bank decision making (the second biggest shareholder is India, with a much smaller 7.6% share of votes). Shareholders are organized into constituencies, which means voting shares can be pooled. For example, the Europe and Wider Europe constituencies have a combined vote share of around 23% if they vote as a block. Notably, the U.S. and Japan, which are top shareholders of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, are absent from the AIIB’s membership.

The AIIB is mentioned in China’s 2015 Belt and Road Vision and Actions document under the pillar of “financial integration” (see China Global Newsletter #3), but it was not established simply to finance “BRI projects.” Indeed, by far the largest recipient of AIIB loans is India, a geopolitical rival of China that has declined to sign on to the BRI initiative or join its Forums.

China’s BRI Leading Group has framed the BRI in terms of its role in increasing the importance of “the international multilateral development system.” This gives a clearer idea of how China sees the bank vis-à-vis the BRI: as a tool for enhancing China’s role in multilateral finance and global governance more broadly. Specific projects that China sees as being especially economically and strategically important are much more likely to be financed by its policy banks (China Development Bank and the Export–Import Bank), whose financing is done on a bilateral level and subject to far less external scrutiny than that of the AIIB.

Although the AIIB has some unique features, in many respects it operates in similar ways to other multilateral development banks. Its staff is loaded with veterans from already established multilateral and commercial banks, projects are proposed by members and generally require approval by the bank’s board, which includes 12 directors representing various constituencies of member countries. Where the bank diverges most from other multilateral banks is in the “lean” nature of both its structure and policies. It has no country or regional offices and just over 300 staff, compared to around 3,600 at the Asian Development Bank, which has 28 resident missions across the region. The AIIB does not have specific country strategies or business plans, and as discussed below, its environmental and social standards are more streamlined than those of other institutions, and it lacks a dedicated gender policy, which puts the AIIB out of step with its peers.

China has no doubt influenced the strategic focus and lean nature of the bank, and both the AIIB and the New Development Bank, of which China is a co-founder, are clear attempts by China to develop institutions in which it has greater sway and can play an active role as standard setter. However, the bank’s modus operandi also addresses the demand of many borrowers. The prospect of a less bureaucratic institution, with policies that place fewer “conditions” on borrowers – including environmental and social conditions – and that deploys capital for hard infrastructure more rapidly, is attractive to many borrowers, as evidenced by the pace at which borrowing members rapidly joined the AIIB.

AIIB Members as of January 2022

Red indicates regional members, blue non-regional members

(light color indicates prospective member still needs to ratify its membership).

>> back to top

How “Green” is the AIIB?

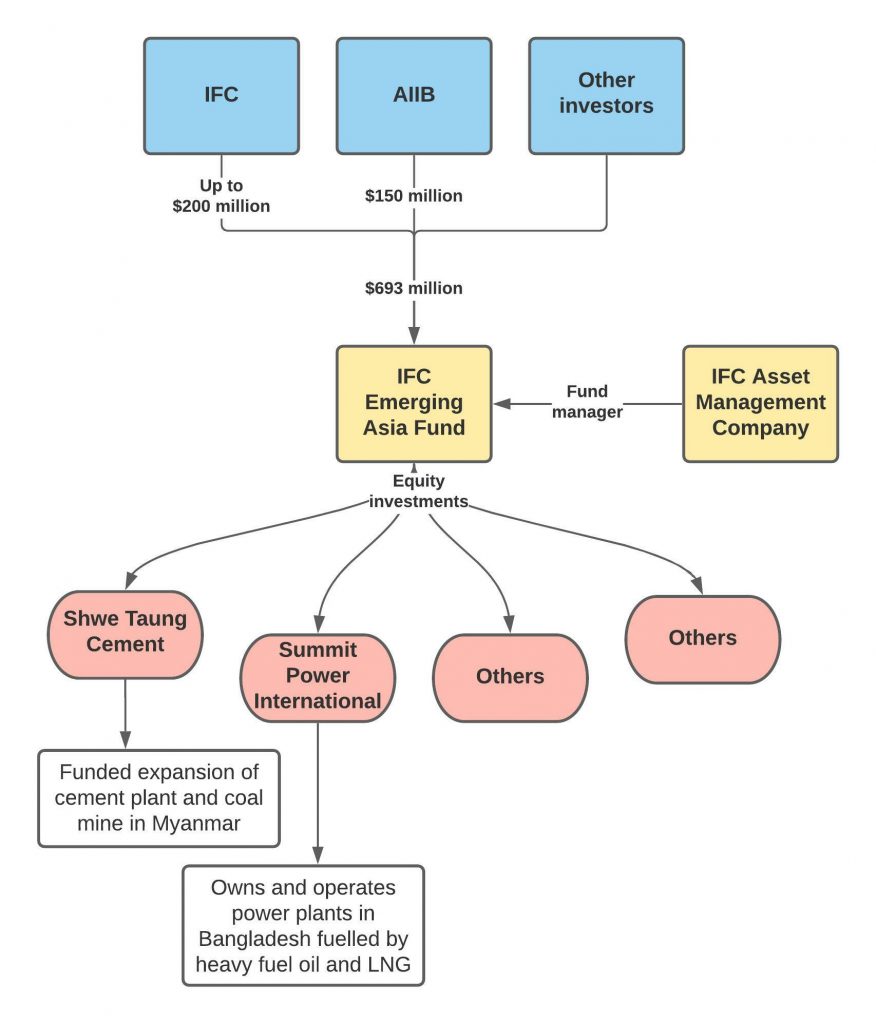

Despite launching as a “green” bank that would invest in clean energy and other infrastructure, in its initial phase of operations, the AIIB failed to live up to its branding. Its energy portfolio has largely focused on gas generation and electricity grids, with limited inclusion of renewable energy projects. Despite lobbying efforts of civil society and some shareholders, the bank decided not to explicitly exclude coal projects, and the climate commitments contained in its Energy Sector Strategy are uninspiring. Although the bank has not directly funded any coal projects, it has financed the expansion of a cement plant and associated coal mine in Myanmar via a financial intermediary (see more below).

Although there is much work to be done, the bank does appear to be shifting. It has increased investment in solar and wind projects, as well as several renewable energy and energy efficiency focused equity funds and investment platforms. In late 2020, the bank published its Corporate Strategy document, which committed to hitting or surpassing a target of 50% climate finance in its overall financing approvals. In 2020, the AIIB categorized 13 projects valued at $1.2 billion as “climate finance.”

In October, the bank announced it would align its operations with the goals of the Paris Agreement by July 2023. To achieve this, the AIIB has stated it will rely on a methodology to be developed by the multilateral development bank Paris Alignment working group, of which it is a member. A month later at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), the AIIB signed on to several joint statements with other multilateral banks on collective climate ambitions, principles for a just transition, and the protection of nature. Civil society groups continue to call on the AIIB and other banks to match these high-level statements with concrete actions. The Big Shift Global Coalition noted that the Collective Climate Ambition “provided few new details, posed no limits on fossil fuel support, and left timelines unclear.”

An important first step from the AIIB will be to address its outlier status among its multilateral peers and adopt an exclusion for coal financing – which is now looking increasingly likely. Although the bank has not explicitly ruled out coal, President Jin has signaled in the past that the bank would not finance coal, with the clearest statement made at an event in 2020 where he said the bank would not finance coal plants or projects “functionally related to coal.” The graphic below was subsequently shared on the AIIB social media platforms and website.

The recent commitment from the Chinese government, the bank’s founder and major shareholder, to no longer finance overseas coal plants, was welcomed by climate campaigners, as well as by President Jin himself, who stated: “This is a bold and consequential step for China, and for the rest of the world. It is also a clear signal of the country’s concrete commitment to global efforts to address one of the most pressing issues of our time.”

With the tide turning against public financing for coal, there were some encouraging signals at the AIIB annual meeting in October, just prior to COP26, that the bank may adopt a no coal policy. The next likely opportunity to formalize this is in the upcoming revision of its Energy Sector Strategy which will begin in early 2022. Although the AIIB and China, at least in terms of its overseas projects, have signaled potentially more progressive positioning on coal investment, an outright exclusion may still be subject to wrangling among shareholders.

Several key shareholders rely extensively on coal power generation and/or have large coal mining industries. This includes borrowing members such as India and Indonesia, but also Australia, which demonstrated its disappointing climate credentials in September by attempting to block a ban on coal at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), despite the fact that Australia represents six Pacific Island nations on the ADB board, all of which are among the countries most vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather events brought about by climate change. It can be assumed Australia will take a similar position at the AIIB. However, it will likely be at odds with many European shareholders and the 14 bank members who signed on to the Statement on International Public Support for The Clean Energy Transition at COP26, which committed to end public finance for unabated fossil fuels by the end of 2022 and was signed by 39 countries and development finance institutions.

Beyond coal, the AIIB has significant investments in natural gas projects, including a major pipeline project in Azerbaijan and a 1,500 MW greenfield gas power plant in Uzbekistan. Excluding gas will be a harder sell to bank members, as stated by Vice President DJ Pandian in November: “Some of our board members feel that we should avoid gas totally, but some countries still demand funds for it … European countries want us to stop investing in such projects.” As a multilateral bank, this will again be subject to negotiation among shareholders, but without a concrete climate action plan and roadmap for getting out of fossil fuels, ramping up investment in renewable energy, and facilitating a just transition, the bank’s goal of aligning with the Paris Agreement will be difficult to achieve.

>> back to top

The AIIB’s Environmental and Social Framework

The AIIB’s core business of financing energy, transport, telecommunications, and water infrastructure is badly needed across Asia and beyond. But the development of infrastructure comes with risks to people and the environment, including forced displacement, destruction of forests and biodiversity, and pollution of air and waterways. In many countries, those who raise concerns or objections regarding investment projects that threaten the rights of communities face reprisals. Since the 1980s, development banks such as the World Bank have required governments and companies to agree to a set of environmental and social standards to secure financing to develop infrastructure projects. While they are not perfect, when applied properly, they help mitigate the harm that infrastructure projects can cause.

With the establishment of the AIIB, there was much concern from human rights and environmental groups that the new bank would trigger a race to the bottom of environmental and social standards. For some, the bank’s “lean” mantra did not bode well and cast doubt on its willingness to conduct the rigorous due diligence necessary to ensure compliance with strong standards to prevent harm. In 2015, a few months before becoming operational, the AIIB began to develop its Environmental and Social Framework. Development of the framework was led by an advisor who had previously worked at the World Bank developing its institutional safeguard policies. Following a contentious initial drafting process, the framework adopted in 2016 was ultimately a scaled-back version of the environmental and social policies of the World Bank. The AIIB reviewed and updated the framework over the past year and a revised version came into force in October 2021.

The World Bank’s environmental and social framework, often viewed as a global standard, contains a broad set of standards to which clients must adhere to avoid and manage risks their operations pose. These standards include tailored requirements in eight areas, including labor and working conditions, resource efficiency and pollution prevention, land acquisition and involuntary resettlement. In contrast, the AIIB chose to impose specific requirements on its clients only in relation to two areas: resettlement and Indigenous peoples. Both frameworks contain a general ‘catch-all’ standard on environmental and social management, but the generalized nature of the requirements, which apply to all types of risk, potentially builds in discretion to decide which types of risks to consider (and which ones to ignore) and how precisely to manage those risks. This is likely to result in weaker protections on the ground and ultimately an increased risk of harm to communities and the environment.

The need for strong safeguards has become clear as the bank has already been linked to several contentious high-risk projects that have come under the spotlight due to their impacts on local communities and the environment. Groups in Bangladesh have raised concerns for years about the Bhola Power Plant, which the AIIB financed as a standalone project, over problems around land acquisition, environmental degradation and unaddressed livelihood impacts. Co-financed projects have also made headlines, including the Amaravati Sustainable Capital City Development Project in India, which the AIIB ultimately dropped after the Indian government withdrew its request for financing from the World Bank, the lead financier, after a complaint to its accountability mechanism alleged violations of environmental laws and land-grabbing. Another World Bank co-financed project in Indonesia, the Mandalika Urban and Tourism Infrastructure Project, has come under fire from civil society groups and received attention from a group of United Nations Special Rapporteurs, Independent Experts and Working Groups, who raised concerns about forced evictions and intimidation, and specifically called out the AIIB’s inadequate due diligence on the project.

>> back to top

Recommended Podcasts

MERICS

The AIIB is more than a China-only story

Gregory Chin (Associate Professor, Department of Political Science at York University)

CSIS ChinaPower Podcast

Yukon Huang (Senior associate in the Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace)

Indirect Financing: A High-Risk Approach

In addition to direct project financing, the AIIB has rapidly expanded its indirect financing through banks, funds and investment portfolios over the past two years, which now accounts for more than a quarter of the bank’s projects. This includes financial intermediary investments and investments in capital markets, both of which are discussed in more detail below.

Financial intermediary lending, which Inclusive Development International has previously described as ‘outsourcing development’, has become increasingly popular in development finance—a trend that accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis, when institutions like the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector arm of the World Bank Group, began to redirect much of its financing away from direct investment in projects and towards commercial banks and private equity funds. These intermediaries then on-lend this financing to end users.

While this approach is justified by the development banks as a way to broaden their reach to small and medium-sized businesses, it also makes it much more difficult to trace funds and ensure that institutional environmental and social standards are met at the project level. For instance, investigations by Inclusive Development International and others revealed that the IFC was exposed to a host of harmful projects via its financial intermediary investments. This included projects linked to land rights abuses, state violence, deforestation, pollution, and a vast expansion of climate-wrecking coal-fired power plants, among others.

Although the AIIB did not originally envision a large financial intermediary portfolio, by October 2021, these types of investments made up almost one-quarter of the bank’s approved projects. They have now become an important tool for realizing the bank’s goal of mobilizing private capital. This increased investment in commercial banks and funds comes with attendant risk. Civil society groups have raised concerns regarding intermediary investments through which the AIIB is exposed to problematic projects in countries including Myanmar, India and Bangladesh, and the risk of the bank supporting fossil fuels via the ‘back door’.

The risks associated with this type of investment were demonstrated this year when the accountability group Justice for Myanmar reported on the indirect exposure of the AIIB to Mytel, a company in which a Myanmar military-owned enterprise and the families of military generals hold ownership stakes.

The AIIB invested $75 million in the Asia Investment Limited Partnership Fund (AIF), managed by a Hong Kong-based firm. The fund’s portfolio includes an investment in Myanmar Fiber Optic Communication Network (MFOCN), which has a business relationship with Mytel. The AIIB responded to concerns of civil society groups, stating that AIF’s investment in MFOCN occurred prior to the AIIB disbursing its investment in the fund. However, it also confirmed that it had conducted prior due diligence of the fund’s portfolio, which presumably raised no concerns, despite the fact that Mytel was specifically identified in a 2019 report by the UN Human Right’s Council’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, which documented Mytel’s military links and recommended against business relationship of any kind with enterprises owned or controlled by the military.

The AIIB’s recently adopted revised environmental and social framework contains fairly robust oversight requirements for financial intermediary investments, relative to other development banks. If these are applied stringently, the bank should in theory avoid exposure to harmful companies and projects. The framework expands the AIIB’s role in reviewing and approving—or excluding—the highest-risk projects from intermediary portfolios and adds important requirements for clients to develop environmental and social management systems. Whether or not the ‘lean’ AIIB will have the capacity to rigorously assess and monitor the potential investments of its clients and reject projects that will violate human rights or damage the environment is yet to be seen. However, civil society groups seeking to hold the bank accountable continue to face challenges in tracing AIIB funds through intermediaries down to companies and projects operating on the ground.

While progress has been made in the way financial intermediary lending is handled under the AIIB’s revised environmental and social framework, the bank is now exploring another form of indirect financing via capital markets. In 2019, the AIIB launched a series of operations aimed at attracting institutional investors to finance infrastructure development in Asia. These operations delegate portfolios to a third-party asset manager, which makes decisions about investments in securities (for example, bonds) traded through capital markets.

As Inclusive Development International has previously written, the AIIB’s revised environmental and social framework expressly excludes capital market operations from its application, meaning that even its truncated standards on environmental and social management, resettlement, and indigenous peoples do not apply to these investments.

The position of the AIIB is that capital market operations cannot be subject to its regular environmental and social accountability system. Instead, it uses ‘Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Frameworks’ to guide external asset managers when identifying and selecting companies in which to invest. ESG began as a rudimentary way for investors to exclude from their portfolios companies that operate in controversial industries, such as tobacco and weapons, and has grown into a complex ecosystem in which dozens of ratings firms score companies using mostly proprietary, big-data methodologies. More recently, ESG investing has come under scrutiny due to a lack of regulation and fundamental flaws in its rating systems and how it is used by asset managers.

Moreover, ESG tools do not function as a risk-assessment and management system; they essentially help investors channel money towards companies that rate well across a range of criteria and limit investment in those that do not. While this may be an important goal for private investors, it is no substitute for the environmental and social safeguards that prevent harms from infrastructure development on the ground.

Although at present the AIIB has only approved four capital market projects, their total value is $1.1 billion, and the approach seeks to crowd in additional finance from the private sector. The bank is in the proof of concept stage, in which it is piloting the projects with a view to potential future expansion. The AIIB’s capital market operations seek to advance the bank’s ‘lean, clean, and green’ strategy, exploring a non-bureaucratic, efficient mode of investment that mobilizes private capital for infrastructure. But while it may be lean, its clean and green credentials are questionable. The challenge of tracing the funds and holding the bank to account to its claims that its investments are responsible is even more pronounced in relation to capital market projects, as the AIIB has so far declined to publish its capital market project portfolios. With no public disclosure of portfolios by the bank, these projects effectively operate in a transparency and accountability void.

>> back to top

Safeguarding the Rights of Those Impacted by AIIB Projects

With a revised environmental and social framework now in effect, attention must turn to implementation. The AIIB has expressed a commitment to learning as it grows, and nowhere is this as important as in environmental and social protection. As the bank’s portfolio expands, it is increasingly financing projects alone—rather than co-financing with other established banks. When the AIIB co-finances projects with other banks, the policies of the co-financier are generally applied, rather than those of the AIIB. Going forward, the AIIB’s environmental and social standards will need to be interpreted and applied by its clients in an increasing number of projects across Asia and beyond.

Adequate disclosure is crucial to ensure that the public is informed when the AIIB is involved in a project—both directly and indirectly. This will require full transparency about projects and companies that receive AIIB support, as well as the recipients of its intermediary lending. The revised environmental and social framework introduced time-bound disclosure requirements for project documents, but also includes broad exceptions to these requirements. A major question mark remains around the bank’s capital market projects. At present, with minimal information available, there is no way for the public to scrutinize the effectiveness of their ESG frameworks. What’s more, because there has been extremely limited disclosure of specific portfolio investments, it is currently next to impossible for the public to trace where funds from these projects are flowing.

Another crucial test of the AIIB’s commitment to responsible and sustainable investment will be the independence and effectiveness of the bank’s accountability mechanism, the Project-affected People’s Mechanism. As its name suggests, the mechanism’s mandate is to receive and address complaints from people affected by AIIB-backed projects. The mechanism, which is yet to accept a complaint, has commenced outreach activities in several countries, but remains relatively unknown. In several areas, it also falls short of the operating standards of the accountability mechanism of other development finance institutions. Worryingly, the AIIB’s capital market operations are immune from accountability through the mechanism.

A recent review of the bank’s portfolio by civil society groups Recourse and Urgewald found that of those projects that could conceivably be subject to an eligible complaint to the Project-affected People’s Mechanism, almost half were financial intermediary projects. A major practical barrier that has potentially limited use of the mechanism is the low visibility of the bank. With no country offices and no AIIB logo displayed on projects that the bank finances, many affected people will have no idea that the project impacting them has AIIB support. This is especially true of financial intermediary projects, whose subprojects can be difficult to identify. In the countries with the most AIIB projects, there is also restricted political space and risk of reprisal against complainants. The mechanism was also not launched until 2019, three years after the bank started lending, although the AIIB has said that it is applicable to all projects retrospectively.

Many of the issues raised in this newsletter link back to the bank’s approach of building a lean institution. China, the bank’s top shareholder is likely a key proponent of lean policies that do not impose unwelcome restrictions on sovereign member countries. But policy developments at the AIIB may also reflect the fact that the bank’s shareholding is structured so that borrowing nations have a greater share of votes than at other institutions. The lean approach of the bank and the stripped-back nature of its policies are likely welcomed by many borrowing member governments, who see bureaucracy at established institutions as cumbersome and imposing unwelcome conditions on them – especially where they seek to establish protections for project affected people and the environment that are stronger than those under their own laws.

A key motivation for many of the European members joining the bank was to influence its policy development, but with a prohibition on non-regional member shareholding rising above 25%, policy outcomes often represent a compromise among members with different priorities, as evidenced in the decision not to exclude coal projects in the energy strategy.

However, if the AIIB is to build a reputation as a responsible infrastructure investor, it will ultimately have to reckon with the fact that high-risk infrastructure projects must have in place the strongest possible social and environmental safeguards and corresponding mechanisms for addressing harms when they occur. The jury is still out on whether its policies and systems are yet up to the task.

>> back to top

Further reading

Chris Humphrey & Yunnan Chen (2021) ‘China in the Multilateral Development Banks: Evolving Strategies of a New Power’, Open Development Initiative.

Natalie Bugalski & Mark Grimsditch (2021), ‘Is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank a Responsible Investor?’, The People’s Map of Global China

Kate Geary & Dustin Schäfer (2021), ‘The Accountability Deficit: How the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s complaints mechanism falls short’, Recourse and Urgewald.

Natalie Bugalski & Mark Grimsditch (2021), ‘The AIIB should include private capital in its environmental framework’, China Dialogue

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.

If you haven’t already, you can also subscribe below to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong.

The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.