China Global Newsletter | Edition 7: April 2023

A Decade in, What’s Next for China’s Belt and Road?

It has been a decade since President Xi Jinping first announced China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), introducing a new framework for the country’s global engagements. Commonly viewed as a vehicle for supporting major infrastructure projects that promote connectivity and trade, the BRI is also the umbrella under which China has signed free trade deals, established new financial institutions, and instituted “people-to-people” initiatives such as organizing study tours and granting scholarships to foreign students. China’s development aid is also frequently framed as part of the BRI.

While there is no official definition or publicly available list of “BRI projects,” around 150 countries, including most of the Global South, have signed BRI cooperation agreements with China, illustrating the significance of the initiative. With this in mind, as the BRI turns ten, we are reflecting on what current trends suggest is in store for the next decade.

Chinese overseas investment appears to be approaching a crossroads. On one hand, there is increasing awareness of the financial, reputational, environmental and social risks that come with overseas investment projects, as well as emerging policies for managing those risks. On the other hand, many of those policies are not yet operational or enforceable, and Chinese companies continue to push forward controversial and high-risk projects such as the East African Crude Oil Pipeline and the Dairi Prima Mineral Mine in Indonesia. Ongoing civil society engagement and vigilance can help ensure that the trend toward risk management and mitigation continues in the right direction. This newsletter aims to provide important context and analysis that can aid in that process.

Contents:

We want your feedback! Please take this brief survey to help us tailor future editions of the China Global Newsletter.

Recent Declines in Chinese Overseas Finance & Investment

While there is a widely held notion that China has been ramping up overseas investment and influence through the BRI, data suggest this investment has contracted in recent years. This contraction is attributable to a range of factors, including increased risk aversion among Chinese stakeholders. While economic factors remain at the forefront of risk assessments, local discontent and international criticism regarding projects that have caused environmental and social harm may be playing an increasingly important role in project decisions.

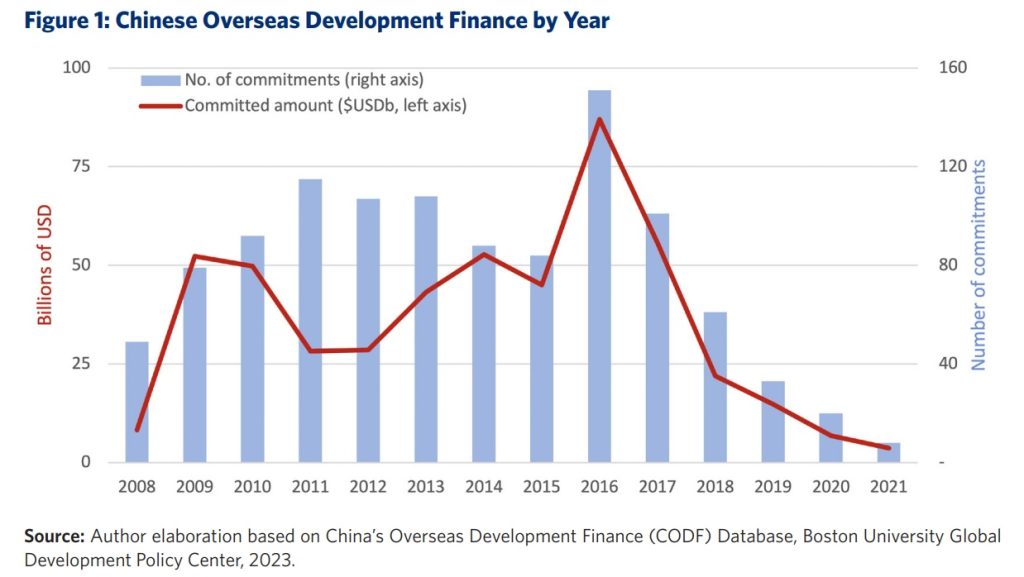

The Global Development Policy Center’s database tracking loans from China’s policy banks (the China Development Bank and the Export–Import Bank of China), has recorded a huge decline in project financing, from 151 projects in 2016 (worth US$87 billion) to just eight projects in 2021(worth US$3.7 billion). Analyses from the center’s experts have also found that in addition to declines in the overall volume of development finance, the average size of loans from policy banks has also fallen.

While it is true, as some critiques have argued, that datasets often do not offer a complete picture—the challenges of obtaining detailed information on Chinese projects and financing means that all datasets will have blind spots and, in particular, there is a lack of comprehensive data available on Chinese commercial bank lending—we think the overall downward trend they suggest is accurate. This is in part because the data we do have on commercial banks, including the Global Development Policy Center’s Chinese Loans to Africa Database, which includes commercial banks’ lending to governments and state-owned enterprises in Africa, show a steep drop in those loans since 2018. One caveat is that Chinese commercial banks, which are important actors in middle income countries, often also lend to the private sector, and there is limited data on those loans. However, while these banks’ global significance has grown in recent years, it is unlikely that commercial loans would fill the gap left by the downturn in policy bank lending, especially for large infrastructure projects in developing countries.

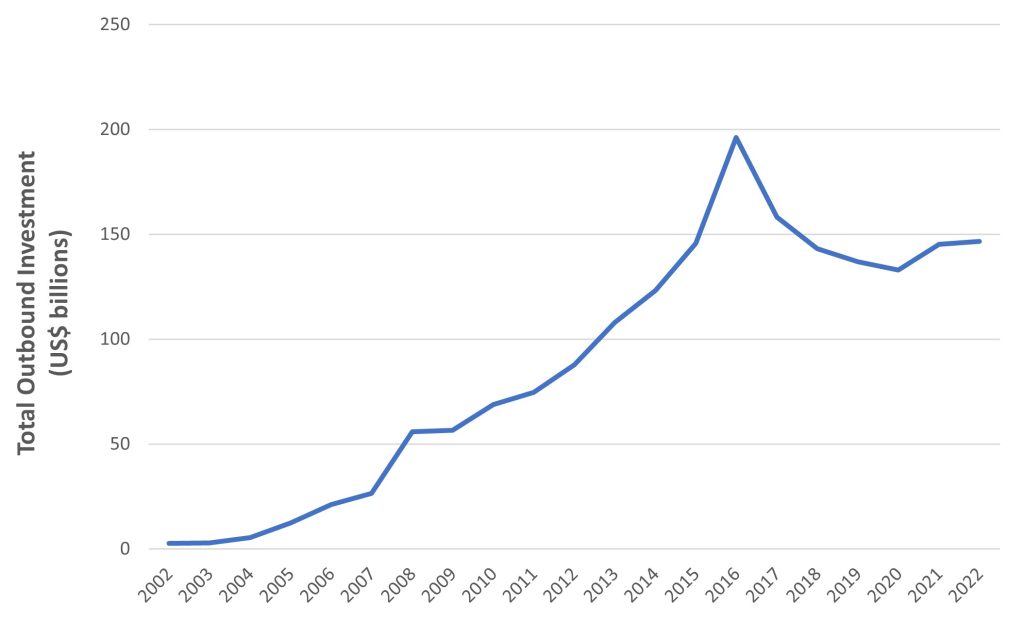

Data from China’s Ministry of Commerce covering approved and recorded outbound investment also shows contraction in recent years, following a spike in 2016.

Source: China’s Ministry of Commerce

Source: China’s Ministry of Commerce

There are many possible reasons for this slowdown. The spike in outbound finance and investment in 2016 coincided with a high current account surplus in China, when it had access to a significant amount of foreign currency. The growth in capital outflows was followed by tightening in controls on foreign investment, an attempt to keep capital in China to fund domestic development (this has likely become an even greater priority in the post-pandemic environment).

Along with concerns regarding capital outflows, Chinese policy banks were having to deal with a large number of high-value non-performing loans, and even before the pandemic, billions of dollars of loan repayments were being renegotiated. At the same time, negative publicity around controversial projects grew, and some projects were stalled, renegotiated or even abandoned due to local discontent. While concerns around economic risks will be at the forefront of policy makers’ minds, the growing focus on the environmental and social performance of Chinese projects has clearly captured their attention, as the reputational and financial consequences of such controversies have become increasing apparent. The drop in policy bank lending and outbound investment coincided in a shift in rhetoric in China, with officials and policy documents increasingly emphasizing the need for “high quality” and “sustainable” overseas projects. The various factors outlined here suggest that China may be seeking to move towards quality over quantity in outbound projects.

>> back to top

Recommended Reading

“Small is Beautiful” A New Era in China’s Overseas Development Finance?

Rebecca Ray, Boston University Global Development Policy Center, provides detailed reflections on the center’s updated dataset of Chinese development finance loans, discussing trends in volume, loan size, geography and sector.

Protecting Biodiversity From Harmful Financing: No Go Areas for the International Banking Sector, Briefing Papers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Friends of the Earth US briefings call on banks to prohibit financing for projects in the Banks & Biodiversity Initiative “No Go Areas,” includes case studies linked to Chinese banks.

Making Moves to Address Sustainability Risk in Overseas Investment

The sustainability risks linked to many overseas investments have become increasingly clear in recent years, as numerous Chinese-backed projects have faced criticism for their environmental and social impacts. Policies for managing and mitigating these risks are emerging, but for the most part are not yet operational or enforceable. Nonetheless, there are signs that there is increasing political will to address concerns, potentially creating greater space for civil society, affected people, and other stakeholders to advocate for progress—including with respect to key issues such as the energy transition, biodiversity, and the debt crisis facing many low-income countries.

While China’s finance and investment, including that regarded as part of the BRI, has helped address gaps in support for global infrastructure, the spike in activity in the 2010s included numerous large and high-risk projects that proved controversial. Some have fallen behind schedule, such as the Jakarta–Bandung High Speed Railway, which encountered numerous problems and attracted criticism for its handling of resettlement impacts. Although due to come online in 2023, the project is several years behind schedule and US$1.2 billion over budget. Others have been dropped all together, such as the Lamu Coal Power Plant, which met fierce local resistance, and was dropped by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China after Kenya’s National Environmental Tribunal revoked its environmental license. At the same time, the pandemic has compounded debt problems in many borrowing countries, leaving them struggling to absorb new loans. This has increased Chinese banks’ and insurers’ anxiety about the risk of default, particularly as they and the Chinese state are also focused on directing capital to addressing the domestic economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kenya Standard Gauge Railway, 2017. (Photo by Mwangi Kirubi)

Kenya Standard Gauge Railway, 2017. (Photo by Mwangi Kirubi)

In this context, there has been a steady trickle of policies and guidelines issued by Chinese state bodies and industry associations over the past ten years that take a more comprehensive view of sustainability risks (for more on this, see Newsletter #6 and our guide on How to Hold Chinese Corporations Accountable). Among the most prominent were the Green Finance Guidelines issued by China’s banking regulator in 2022, instructing banks to develop and staff the systems necessary to properly assess and manage sustainability risk, and calling for banks to establish grievance mechanisms to deal with complaints from affected people. Despite these positive steps, there is a sense of fatigue among many civil society groups who have been monitoring these developments for years and are still awaiting more concrete steps to ensure implementation of these policies, improve transparency, develop better communication channels, and establish comprehensive mechanisms to manage environmental and social impacts of overseas projects.

There are several areas where there is reason to believe there will be increased activity and potential opportunities to influence how risk management takes shape in the coming years. These include: 1) investment in fossil fuels and other high-risk energy projects, 2) securing critical mineral supplies to fuel renewable energy solutions, 3) protecting biodiversity and following through on commitments from the China-hosted COP15 biodiversity summit, and 4) confronting the debt crisis in low-income countries and its links to foreign lending.

High-risk energy projects and China’s “no coal” commitment

Global power projects, including fossil fuel, hydropower and renewable energy, have been an important focus of Chinese overseas investment, with Chinese firms and banks becoming key players in the development of global coal plants over the last few decades. China has committed in recent years to cease support for new coal plants and step-up support for green and low-carbon energy. This has been articulated in policy documents, but there are concerns that grey areas in these documents leave the door open to further coal expansion.

In 2021 President Xi announced that China would no longer build new overseas coal plants. Groups monitoring how this pledge has been implemented have found that a significant number of planned overseas coal plants have been shelved. Several key actors, including Bank of China, China Eximbank and Sinosure announced they would no longer support new plants. In early 2022, China’s top planning agency issued a policy confirming that building of new overseas coal plants would cease and that plants “under construction” should move forward “prudently and cautiously.” Several projects that were in preparation, such as the Ugljevik III power plant in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone in South Africa, have since fallen through. China Huadian, one of China’s major state-owned energy corporations stated, without detailing the plan or timeline, that they have withdrawn from the 700MW Jambi-2 coal power project, although a power purchase agreement was signed in 2019.

Although this shift is welcome, grey areas in the coal plant commitment have been flagged by civil society observers. There are questions around what will happen with projects that have secured financing but not yet started construction, whether Chinese firms will be able to continue to sign construction and equipment contracts for coal plants, and how “captive” coal plants (those situated in and serving industrial zones, for example) will be impacted. Since the commitment, state-owned enterprises have signed contracts for construction, equipment supply and design of at least four plants in Indonesia and Laos, indicating that in some circumstances some types of activity may continue.

In addition to its ongoing (if diminished) investment in coal, China is also the world’s top dam builder, and regards large hydro projects as renewable and green energy sources, meaning Chinese companies and banks will continue to invest in these areas and be exposed to the associated risks.

While China has become a leader in global solar and wind power projects, there is much scope for further expansion of this, and as the next section details, renewable power projects come with their own environmental and social risks.

Construction of the Nam Ou 3 Dam between Muang Khua and Muang Ngoi Neua, Laos (photo by Christophe95).

Construction of the Nam Ou 3 Dam between Muang Khua and Muang Ngoi Neua, Laos (photo by Christophe95).

Potential pitfalls in the global energy transition

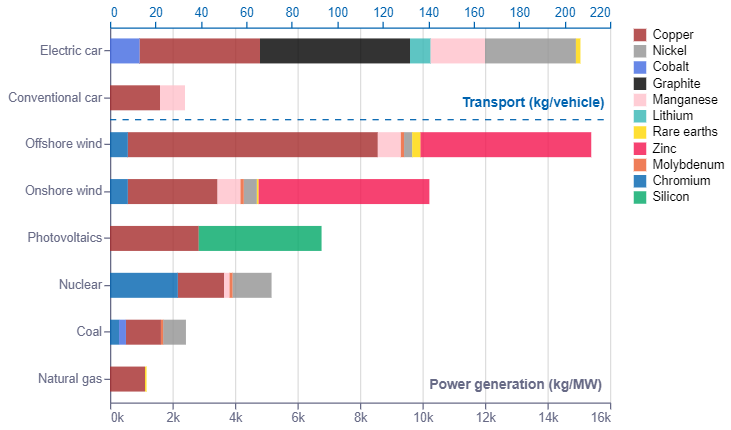

As the world responds to the climate crisis and China expands its investment in alternative and renewable energy generation, it is increasingly seeking to secure the resources necessary to facilitate this. In particular, China (among others) is focused on ensuring a sustainable supply of “transition minerals” required for the production of solar panels, wind turbines, car batteries, and electric or fuel efficient vehicles.

Source: Economic Observatory / IEA

Source: Economic Observatory / IEA

Chinese firms are active at all stages of transition mineral value chains. For example, in Indonesia, Chinese firms mine nickel, which is then processed at major industrial parks in Sulawesi and eventually purchased and used by car companies in electric and hybrid vehicle batteries. Chinese mining and mineral processing firms supply Chinese companies that are developing renewable energy solutions, but also trade extensively on global markets, providing the inputs to transition industries the world over. These commodities therefore have huge economic value, in addition to being crucial to China’s own domestic energy transition. The government has prioritized enhancing the resilience of its supply chains for products such as electric vehicles and photovoltaic panels, and has identified investing in overseas mineral resources as crucial to guarantee these supply chains.

Transition mineral mining and processing comes with significant social and environmental risks and impacts (as well as associated financial, legal and reputational risks), which are increasingly well-recognized as these projects expand to meet growing demand.

In Indonesia, development of the massive Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park has raised concerns about pollution, biodiversity loss and worker safety. Protests at a nickel plant in another industrial zone in January 2023 led to the death of one Chinese and one Indonesian worker. In copper-rich Peru, major Chinese-invested mining projects such as the Toromocho Copper Mine Project and Las Bambas Copper Mine have been beset by protests and resistance from local communities, resulting on numerous occasions in the cessation of operations in the case of Las Bambas. Cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo has become notorious for child labour and links to conflict, leading to severe reputational harm for implicated firms from China and elsewhere.

As we’ve outlined in a previous newsletter, the aluminum industry (a key input for electric vehicle production) is also reckoning with its social and environmental footprint. In Guinea, Chinese and other global firms competing for access to the world’s largest reserves of bauxite ore (the raw material used to produce aluminum) are facing repercussions for irresponsible mining and business practices. Australian and U.S. firms are facing demands from local communities to address harms, and the Société Minière de Boké (SMB) mine, owned by a Chinese-Singaporean consortium, is also involved in conflict with local communities due to its handling of impacts related to resettlement, water access and pollution. Chinese firms are heavily invested in Guinean bauxite, with more projects under development and significant resources already invested in infrastructure aimed at facilitating the expansion of the industry, so this will continue to be an important area in which Chinese stakeholders must enhance implementation and oversight of projects.

In 2022, China’s environment and commerce ministries updated their guidelines on environmental protection in foreign investment, which included specific, although brief, provisions calling for companies to pay close attention to risk management at various stages of the mining project cycle. Additionally, for several years, the Chinese industry association, the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals and Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC) has been encouraging Chinese firms to apply its social responsibility and due diligence guidelines to overseas mining and mineral supply chains.

The CCCMC also established the Responsible Cobalt Initiative, which recently became the Responsible Critical Mineral Initiative (still referred to using the original acronym, RCI), which seeks to address social and environmental risks in cobalt and other mineral supply chains. In late 2022 it released a draft complaints mechanism, which when adopted will be the first accountability mechanism established by a Chinese industry association allowing communities to raise concerns about the impacts of an overseas mining project. While this is an important development, there are key aspects in the draft that need to be strengthened to ensure the mechanism is effective and can gain trust from all stakeholders.

These developments represent an acknowledgement in China that implementation of overseas mining projects needs to be improved, but further concrete steps will be required, especially as Chinese firms find themselves increasingly subject to the sustainability requirements of global supply chain partners.

Biodiversity risks and commitments

Mines, transport corridors, hydropower dams and other industrial and infrastructure projects—the sort of projects often linked to the BRI and other Chinese overseas investment—inevitably come with biodiversity risks that Chinese and other developers are increasingly under pressure to address. This issue was in the spotlight in 2022 as China co-hosted the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15). In advance of the event, a group of 90 civil society groups from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the world wrote a letter to the co-chair calling on Chinese authorities and project stakeholders, including banks, companies, contractors, and other developers to protect biodiversity and people in its overseas investments. The letter included a list of 37 controversial projects with Chinese involvement that are associated with harmful biodiversity, environmental, and social impacts. This is not just an issue facing Chinese stakeholders—civil society groups also addressed letters to commercial banks and financiers and all state parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity calling on them to reverse the biodiversity crisis.

COP15 closed with the signing of what was described as the “landmark” Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which set out goals and targets for halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030. It includes a commitment by all parties to align public and private financial flows with the framework’s goals, and includes the specific target of taking legal, administrative or policy measures to encourage and enable transnational companies and financial institutions to monitor, assess, and transparently disclose their risks and impacts on biodiversity and progressively reduce negative impacts. Prior to COP15, recent guidelines from China’s banking regulator, commerce and environment ministries stressed the need for biodiversity protection in development projects, but the important work of operationalising these commitments now falls on Chinese regulators and those companies and banks active globally.

The Nile at Murchison Falls in northern Uganda (photo by Babak Fakhamzadeh)

The Nile at Murchison Falls in northern Uganda (photo by Babak Fakhamzadeh)

Confronting the global debt crisis

One issue that has become central to the discourse around the BRI and Chinese lending in general is that of debt. The “debt trap” narrative, in which China is accused of burdening borrowers with unpayable debts in order to seize assets or increase its influence has been vigorously debunked, but the issue of borrower debt distress is very real. This has been building for several years, but the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have brought it to the fore. Major recipients of Chinese finance, including Laos, Zambia, Kenya, and Sri Lanka, are facing severe debt distress and having to negotiate with creditors how to service debts that are due. These debts are owed to a wide range of creditors, including Chinese banks, and debt sustainability will no doubt factor heavily into decision making by both borrower countries and Chinese financiers when considering new loans, especially for large and high-risk projects.

At a forum in Beijing in late 2022, Jin Zhongxia, director general of the People’s Bank of China’s department of international affairs hinted that policy reforms at China’s policy banks could help mitigate this crisis. While laying blame primarily on debtor countries’ “reckless” handling of their debts, as well as an overabundance of credit in the post-global financial crisis period and the impacts of the pandemic and war-induced inflation, he also said that China’s policy banks could “perhaps” carry out reforms that increase transparency in their lending businesses (for more on Jin’s speech, see this Panda Paw Dragon Claw article).

Although borrowing countries in many cases must be accountable to their citizens for fiscal mismanagement, there is plenty of blame to share, and the reforms hinted at by Jin should be a key priority for China. Borrowing nations’ lack of transparency is often a serious concern, but an analysis by AidData and others of 100 publicly available Chinese loan contracts found widespread inclusion of confidentiality clauses that bar debtors from disclosing contract terms or related information unless required by law. As long as this lack of transparency persists, efforts to increase the sustainability of Chinese projects will remain hampered.

>> back to top

Looking Forward

The decline in China’s outbound investment and policy bank finance witnessed in recent years is the result of numerous factors. Non-performing loans and rapid capital outflows led to greater caution in China, along with enhanced consideration of the economic and political risks associated with major overseas projects.

The fallout of poorly managed environmental and social risks has impacted local people and the environment, as well as the reputation of Chinese developers and investors, and the success of their projects. It can be seen in statements and polices coming out of China that there is a realization that systems to enhance management of these risks need to be improved. While there have been some important steps forward, it remains to be seen if these concerns are prioritized to the same extent that financial concerns have been. Statements and policies are important, but implementation is often still lacking.

Global projects will continue to be crucial for China, such as projects that bolster access to resources for transition minerals, to name just one example. However, as China seeks to boost the domestic economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it can be assumed that there will continue to be scrutiny of capital outflows, especially into risky areas and projects. Additionally, the heavy debt burden that many countries currently face may dampen enthusiasm on both sides to move forward with some high-value and high-risk projects. This could potentially create greater space in which due diligence, management systems, communication channels and grievance mechanisms can be enhanced and adopted. In this moment it is as important as ever that global civil society groups, especially those in the countries hosting this investment, continue to document concerns, communicate them to Chinese stakeholders and the public, and advocate for improved practices that ensure the protection of both local people and the environment.

>> back to top

Further reading

With global mining companies’ human rights due diligence struggling to keep pace with the transition mineral boom, this tool from Business and Human Rights Resource Centre tracks the companies involved and their links to allegations of rights abuses.

New mechanism could strengthen accountability of China’s mining projects

Inclusive Development International & Accountability Counsel on how a planned complaints mechanism for overseas mining could help close the accountability gap, if designed and implemented well, for China Dialogue.

You can read previous editions of our China Global Newsletters here.

If you haven’t already, you can also subscribe below to receive an email alert when our next newsletter is published.

This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of Oxfam Hong Kong.

The contents do not necessarily reflect the position of Oxfam Hong Kong.